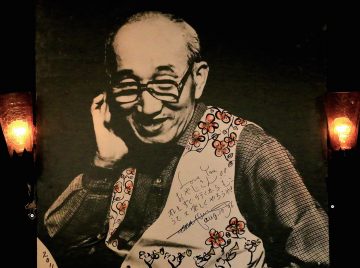

A conversation between Satoshi Ichiyanagi and Yoshio Otani - Satoshi Ichiyanagi seen by artists of different generations -

From the postwar period to the present, Toshi Ichiyanagi has traveled back and forth between Japan and the United States, constantly pursuing new forms of expression through music. He has developed his own unique style of expression while building friendships with artists from various genres, and even now, 80 years after his birth, he continues to energetically create works.

On the other hand, Yoshio Otani was born in Japan during the period of rapid economic growth and is also active across genres. In his books, he symbolically refers to music criticism in the 20th century after the birth of recording media, and has a unique perspective on the relationship between society and music.

Through this dialogue between two musicians from different generations but living in the same era, we hope to gain a new perspective on Ichiyanagi Satoshi, as well as a sense of the atmosphere of their respective eras.

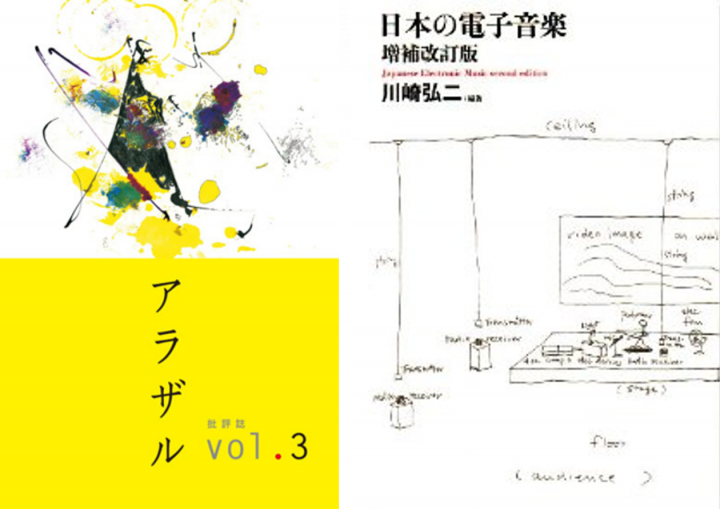

Yoshio Otani (hereafter, Otani ): Nice to meet you. I'm glad to meet you. I was interviewed here (pointing to "Alazar Vol. 3" [a hardcore independent critical magazine. Vol. 2 features Yoshio Otani, and Vol. 3 features Satoshi Ichiyanagi]) in the issue before Ichiyanagi's. It's a very long interview and well worth a read. I'd been reading this even before I was approached about the interview.

Ichiyanagi : No, no, it’s probably best not to read that. (laughs)

Otani : I was also involved in the launch of a book called "Japanese Electronic Music." I also did some interviews.

Left: "Arazar" Vol.3 Right: "Japanese Electronic Music" by Koji Kawasaki

Ichiyanagi : But it was an incredibly detailed book.

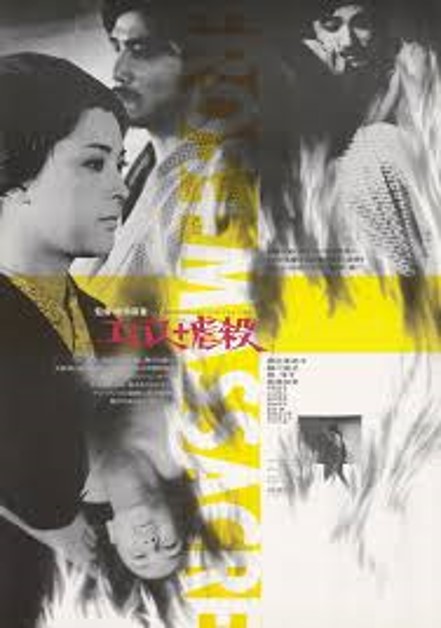

Otani : We started researching in the 1990s what kind of works were created and how they were demanded in the early days of Japanese electronic music, that is, up until the 1970s, but at that time there was almost no comprehensive information, so we researched and archived Japanese music from before the 1980s, such as the music for Ichiyanagi's "Eros + Massacre" [Director: Yoshishige Yoshida / Music: Satoshi Ichiyanagi], one by one. Finally, in the last 10 years or so, information from the 1950s and 1960s has started to appear, and we are now able to talk to people like this.

"Eros + Massacre"

■ Live music/recorded music

Otani : It was around the '90s when I was still in my 20s, and when I wanted to listen to Japanese avant-garde music, there was a long period of time when reissues of recordings had not yet progressed and I was unable to listen to it.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, up until the early ’90s, Japan was on a steady rise and there was a lot of live music. We’ve grown up in that sort of environment, so in some ways we’re not as good at dealing with it now.

Otani : Oh (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : That’s right (laughs).

Otani : I think that even classical musicians nowadays tend to listen to playbacks first, rather than experiencing music live...

Ichiyanagi : That's true now, but won't that lead to a deterioration of our hearing?

There was a time when LPs were around, and some critics were pleased that CDs sounded clearer than LPs when they listened to them, but with CDs you can't hear what's going on, that is, it may be pleasant to the ear, but you can't hear how it's being played. For example, when playing the violin, you can hear the bowing, and other such small details on LPs. Even now, if you go to Europe, there are still quite a few stores that sell LPs rather than CDs. In Japan, that situation is almost nonexistent.

Otani : That's right, I've heard that CDs are no longer selling either.

Ichiyanagi : But it's still better than America.

Otani : CDs are hardly sold in America anymore.

I was part of the CD generation, and the media switched when I was in elementary school. It seems like we've moved on to a different medium in the 30 years since then, but were records around when you started making music?

Ichiyanagi : No, it was very limited in Japan. When we were children, the scars of the war were so great that almost everything was gone. There were no instruments, no sheet music, etc. In those days, there were very few people playing music, and as you know, there were only about three concert halls at that time.

Otani : Lol

Ichiyanagi: The only large hall we had was Hibiya Public Hall. Even so, perhaps because there weren't many halls, there was a lot of enthusiasm and it was always full. Nowadays, there are so many events that we don't have any idea how to fill them with content. Our generation knows both, so it's hard for us to accept this shift.

Otani : But it feels strange to say it's difficult to fill in the gaps.

Ichiyanagi : It's very strange. There's no other country with so many beautiful halls. Someone from the Vienna Philharmonic came by the other day and told me that all the tickets for their opera and orchestra concerts for the next three years are completely sold out.

Otani : Oh, so that's three years?

Ichiyanagi : But the venues they’re holding them in are all old. They care about the content, so they have impressive names like the Mozartsaal or the Schubertsaal, but the halls are really just lofts.

Otani : They won't be building any new halls.

Ichiyanagi : It seems they aren’t very interested in that.

Otani : That's right.

I went to the "Experimental Workshop" exhibition the other day, and the members of the Experimental Workshop were active from 1976 to around 1983, and it seems as though Ichiyanagi moved to New York around that time, almost at the same time as them.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, I know almost nothing about the early days of Jikken Kobo.

Otani : Around where the Setagaya Art Museum is now, people would walk to their friends' houses, and if they found someone they were interested in on the street, they would become friends and exchange works of art. I thought that was an interesting exchange (laughs).

Ichiyanagi : Yes, walking, meeting people and interacting with them was a part of my daily life. A little after Jikken Kobo, critic Yoshida Hidekazu set up the Institute of 20th Century Music, which planned a festival in a different location every year. It was at this festival that the idea of playing American music first came up, which was what prompted me to return to Japan in 1961.

Otani : It was around '53 when Hidekazu Yoshida was touring New York and Europe. Did you not meet him in New York?

Ichiyanagi : I guess we didn’t quite meet up, but I did meet Takahiro Sonoda and Toshiro Mayuzumi.

Otani : I believe John Cage was introduced to Europe around 1954 or 1955.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, in ’54.

Otani : Hidekazu Yoshida wrote that Cage's music was indeed quite difficult to accept at the time.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, that’s true. But then you toured Europe around ’54, which opened up your horizons to a lot more people there, and you soon began to have connections with Boulez and Stockhausen.

■Standing between the East and the West...

Otani : Cage's music was introduced to Japan when Ichiyanagi returned to Japan, but up until that point, there was still an era in which new schools or new methods of contemporary music were emerging. I still can't understand from reading the materials whether Cage's music was perceived as something new when it was performed on stage, or how the audience reacted to it. I would like to hear your thoughts on this.

Ichiyanagi : In those days, aspiring musicians and audiences alike were full of a hunger for success due to the effects of the war, and looking back on it now, it was a rare, open and free time in Japan, so everyone was very interested. I think there was a feeling that if we didn't keep up, we'd be left behind.

However, I don't think Europe, at least in terms of music, has much of a perception like that.

From around 1950, Daisetsu Suzuki taught Zen at Columbia University in New York, and Zen, in his words, is "everything that is here and now." In other words, the most important thing is to be here and now, without doing anything. Cage's music made this into a philosophy, and he created graphic scores and other things to embody it. I think that was very difficult for Europeans to understand at first.

In Japan too, after the war there was a lot of backlash against things Japanese, so there was a certain idealism and hunger for cutting-edge things, but it felt like these Japanese perspectives were pretty much discarded.

Because I took the position that the East and the West could coexist and interpenetrate, I found it difficult to devote myself entirely to Zen.

Otani : I think that at that time Cage's music was introduced to Japan as American music, but to what extent did the audiences at the time accept the information or impression that it was based on Zen?

Ichiyanagi : This is just my opinion, but the critic Kuniharu Akiyama, who has written about and interacted with Cage and has considered him the most important composer for a long time, and I just couldn’t agree on that one point.

Otani : A little more about that... (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : Mr. Akiyama evaluated Cage from a European avant-garde perspective that completely excluded anything Japanese or Zen. I feel that that's not quite enough... I was supposed to be Cage's student, but his way of educating me was to hang out with him, hold concerts together, help him compose, and often live with him, so I was able to get a sense of what he was thinking. Being with him in an environment that was different from ordinary music education, I gradually came to realize that Japanese issues were important.

Otani : I see. So that means that you moved to America and that's when you started to distance yourself from Japan?

Ichiyanagi : That’s right.

Otani : When I read Akiyama Kuniharu's criticism from that time, I get the sense that he had an incredibly greedy desire to incorporate Western music.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, that was an important thing and I was very glad that they did it, but it’s also true that I had been away from Japan for so long that I became more and more interested in the different ways of thinking and characteristics of Japanese arts and culture than those in the West.

Otani : Your writing also expresses the feeling that if you tried to incorporate something, it would be met with the response, "This is Japanese," which was quite a shocking feeling in the 1960s.

When I read the literature from that time, I see Cage described in broad terms as being "based on Eastern thought," but I get the impression that he didn't clearly appeal to a Japanese audience as being Zen or koan [a problem given to a practitioner in Zen Buddhism as a tentative goal for attaining enlightenment].

Ichiyanagi : Maybe it’s because Japanese society is vertically divided, so art and life are separated, whereas in America Zen is seen as a part of life.

When Cage first came to Japan in 1962, the first thing he said was that he wanted to visit Daisetsu Suzuki. So I took him to Tokeiji Temple in Kamakura, where Daisetsu was 92 years old at the time, but he was very lively. And, really, how can I put it... Cage was completely...

Otani : It was like, "Master!" (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : That's right, it was like, "Master!!" (laughs) And Daisetsu was very confident. He spoke English fluently, of course. On a side note, what surprised me the most when I went there was an incredibly beautiful woman in her mid-twenties who seemed to be Daisetsu's secretary. I wondered who she was, but it turns out she had been devoted to Daisetsu's Zen since the age of 12, and had accompanied him when he returned to Japan.

Otani : Oh!

Ichiyanagi : She’s still here. I met her in Kyoto the other day for the first time in about 50 years. She’s still a very beautiful woman, but she’s also a strict person. (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : Cage incorporated many things he learned from Suzuki into his own music, and all of those things were reflected in his subsequent works, so I think he probably wanted to meet him first and foremost. But that was also his last time, as Suzuki passed away at the age of 96.

■ Influence of the times

Otani : Cage's youth was during the Great Depression, and listening to stories from his youth, it seems that he aspired to be a composer while working part-time jobs, and studied with Schoenberg, during which time he made various discoveries and came into contact with Daisetsu's Zen. In a similar way, Ichiyanagi also lived in New York in the late 1950s and Japan in the 1960s, studying at the Juilliard School in the US, where he encountered Cage, and then returned to Japan. I would like to hear about the influence of the times on his studies there, and any stories from that time that you may have.

Ichiyanagi : The American music world is clearly divided into three parts: what we call in Japan the music world (orchestras, operas, and music schools), university music departments, and freelancers who don’t belong to any group.

For example, in Japan, Takemitsu composed about 70 to 80 film scores, and Mayuzumi and Hikaru Hayashi also composed many, and in a sense, there are very strong ties with specific directors. However, even though so many films are made in Hollywood, a composer who once stepped into the film world would never be welcomed into the music world or become a university professor. That's how clearly it is distinguished or discriminated against from art music.

Otani : So the distinction between academic and popular works, in other words a certain hierarchy, was clear. Was that the case in the 1950s as well?

Ichiyanagi : That was certainly the case in the '50s. For example, Steve Reich came to Japan recently, but he never used orchestral players. So he works with a group of people he selects himself. That in itself creates a society where freelancers can get by.

Otani : Did Merce Cunningham's dance company also perform as an independent company?

Ichiyanagi : I don’t know much about the inner workings of dance, but I think it was consistent from start to finish. Cunningham was into modern dance, before that there was modern ballet, after Zo it was contemporary dance, etc.

Otani : For modern dance, I would go with Martha Graham.

Ichiyanagi : Yes, it is quite subdivided.

Otani : Before Graham, were classical musicians still being used?

Ichiyanagi : Mainly American contemporary composers of the time.

Otani : Just like with film, has no one in the music world or at universities done any work related to contemporary dance?

Ichiyanagi : I wonder about the dancing. But there were a few.

My impression was that contemporary dancers use music by contemporary composers, and I got a strong sense that dance and music are living in the same era.

Otani : Compared to film, was it recognized to some extent as a stage art?

Ichiyanagi : I would say that dance is an important part of performance art over there, alongside music and theater. In that respect, I find the recent trend of using classical or pop music for dance new though somewhat odd.

Otani : You began your career in the United States at the Juilliard School, but did you have any intention of entering the music world?

Ichiyanagi : No, I just wanted to go to New York, and as a foreigner you have to belong to some institution in order to get a visa. The easiest thing to do was to go to school. But I hardly ever went to school at all. (laughs)

Otani : I see (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : The whole of New York is like a school. And another reason was that there was no teacher at Juilliard who taught the 12-tone technique.

Otani : Oh! Is that so...?

Ichiyanagi : Right. So, as you can see from their attitude, freelancers in particular were excluded.

Otani : So it's the same in America. I often hear stories like that in Europe.

Under those circumstances, was it before you returned to Japan that you decided to pursue a career as a freelance composer rather than go to Juilliard?

Ichiyanagi : I had been composing music using the 12-tone technique since I entered Juilliard, so piano was the only thing I studied hard at there.

Otani : Were you not particularly interested in becoming a pianist?

Ichiyanagi : Since my main focus is on composing, I don’t have much time.

Otani : I see. So originally you went abroad to study composition.

Ichiyanagi : Yes. I don’t mean this in a bad way, but musicians are quite similar to athletes in some ways.

Otani : Yes (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : They hardly ever ask why you're doing it or anything like that.

Otani : Yes, basically, players can play without thinking about the song.

Ichiyanagi : That’s right.

Your CD "Jazz Abstractions" is very interesting. Are you still performing it live?

Jazz Abstractions

Otani : Jazz Abstractions is mostly a collage, a compilation of music using existing sound sources. I'm a saxophone player, so I do a few pieces of jazz live performances, and I write songs. I often get work for plays and dramas, so I create music for them, and I also write jazz, soul, and hip-hop music in the so-called black music genre, and I also play improvisations as an improviser using electronics and saxophone.

Ichiyanagi : Is the number of members always the same?

Otani : My own band is a fixed group of three people, but the rest of us go back and forth and perform in various places... The other day I teamed up with the butoh dancer Ko Murobushi at the Red Brick Warehouse, and we created a piece combining his dance with my music.

Ichiyanagi : That must be fun and exciting. So you’re operating in a very original way.

Otani : Yes, I'm going to try my best (laughs).

■ Connection with black music

Otani : The 1950s was the time when modern jazz was at its most popular, especially in New York. What did the bebop sound of jazz sound like to your ears at the time?

Ichiyanagi : I would occasionally go to places like the Village Gate and the Village Vanguard in New York, and it was Tudor, who worked with Cage, who gave me the opportunity to go there. He would hold concerts at those venues.

Otani : Tudor?!

Ichiyanagi : Actually, Cage’s first official venue was the Village Vanguard.

Otani : It was the Village Vanguard?!

Ichiyanagi : Around '58, Tudor gave a recital at the Village Vanguard. Of course, no one had played that kind of music there until then, but it became a little easier to go there after that. But as for its influence on me, I didn't have much time for it. The reason is that America was pretty much the only country that had won the war at the time, and so many musicians came from Europe, and I had a lot of contact with them. So I'd say that after the '60s, I was more into rock and contemporary music than jazz (laughs).

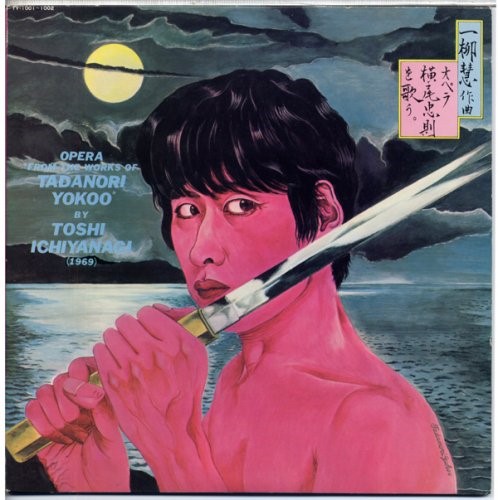

Otani : For example, "Singing the Opera Tadanori Yokoo."

"Singing the opera Tadanori Yokoo, composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi"

Ichiyanagi : The word “progressive” is used for both rock and jazz, right?

Otani : In jazz, the word "progressive" was used for a time, for example by the latter half of Stan Kenton, and in much the same way as the term "third stream" [a jazz movement that sought to fuse with classical music]. Gunther Schuller and others started using the term "progressive jazz," but it never caught on.

Ichiyanagi : I see. How would you describe Cecil Taylor?

Otani : When Cecil Taylor first came out, he was considered part of the progressive jazz genre, but after Ornette Coleman came out, that genre was seen as the cutting edge of black music, and the term free jazz came to be used, and the term progressive jazz was dropped at that time.

Ichiyanagi : I see.

Otani : From the mid to late '50s, there was a trend towards a fusion of contemporary music and jazz, with a strong emphasis on arrangement, ensembles, and the inclusion of 12-tone sounds. I had the strong impression that this was a form of jazz that was imported from Europe.

From the perspective of black music, there was swing music, which is a form of popular American music, but from the 1940s to the 1950s, a type of music called bebop emerged that was based on improvisation and had a strong combative nature. Did you ever notice the difference between these two types of music in America in the 1950s?

Ichiyanagi : Hmm, I wonder what I was doing then… I had a lot of contact with people in the art world and dance artists, so I wasn’t really involved in music.

Otani : I see (laughs)

Ichiyanagi : Also, this wasn’t something I was immediately conscious of, but as I said before, each genre of music had its own borders, but art transcended those boundaries and produced new works one after another, and freelance musicians were heavily influenced by it.

Otani: Yes, that's right, it was also the heyday of Jackson Pollock.

Ichiyanagi : That’s right.

■ Working in a variety of fields

Ichiyanagi : Young people in Japan today tend to follow the same approach as you did... But Takahashi Yuji is one too.

Otani : Ah, I see.

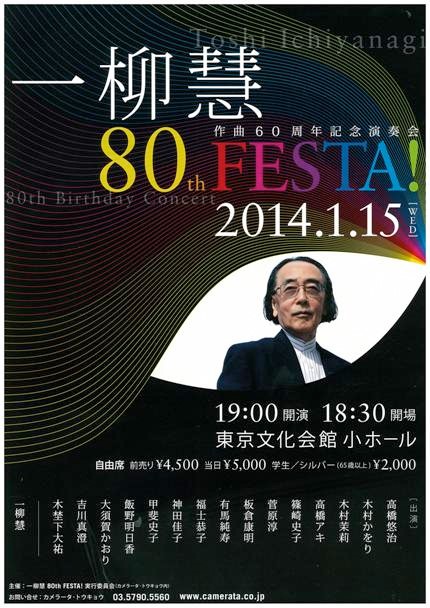

Ichiyanagi : We're having him perform at a concert next month [to be held at Tokyo Bunka Kaikan to celebrate the 80th anniversary of Ichiyanagi's birth], and he's just as busy as Otani is now. He's working with dancers, poets, all kinds of people, and he seems to be in a really good mental state. He looks like he's having fun.

"Ichiyanagi Satoshi 80th FESTA!" flyer

Otani : For composer-players who can also play instruments, the increased opportunities to play with different people are good for your health (laughs).

Ichiyanagi : Yes, I think so too.

Otani : It's common for people of my generation to end up confining themselves to a certain genre, and I didn't receive a proper academic education, so inevitably there are no other places for me to work than with people in the theater or literature fields.

Ichiyanagi : But I think there is a great possibility that such an approach will become more open.

Otani : Yes, that's right. The basis is to work with people who seem interesting.

Ichiyanagi : What I dislike most is how everything has become vertically divided and the system has become so rigid. It has its merits, but it also means that the space in which you can move freely is very limited.

Otani : I think that's natural.

Ichiyanagi : Yes.

Otani : Many players feel the same way. It's the same with jazz musicians, but classical musicians of my generation don't want to get involved at all... The theater and dance scenes have been really interesting in recent years, and I think it would be great if more people got involved in those areas.

Ichiyanagi : It's the same with theater, dance, and hopefully music too, but among the few performing arts out there, music is the only one that's a bit too rigid. Everyone is very talented, but as I said before, they're becoming more like athletes and less flexible.

Recently, I met Masahiro Miwa. He seems to have also shifted away from the music industry.

Otani : I see, there has been a shift.

Ichiyanagi : I met her when I saw her production of Tokyo Rose, and I was a bit surprised to hear that she had also shifted from visual arts to theater.

Otani : I think that theater and mixed media are the fields that still have a lot of potential, and that makes me really want to work with you, but was that kind of feeling also very prevalent in New York in the 1950s and 1960s?

Ichiyanagi : I think it was pretty much that kind of atmosphere.

However, what surprised me a little was that when I returned in 1961, although there were limited places available, there was something called the Sogetsu Art Center, and in that sense, that was the only place that was truly free.

Otani : I've heard a lot about it. Looking at the documents, I see that there are paintings by Sam Francis.

Ichiyanagi : At the previous Sogetsu Hall, one of them was Sam Francis and the other was Mathieu. I hope that dream comes true again.

Otani : That's right. When I listen to you talk, I wonder if it's okay to do so many different things.

Ichiyanagi : You're right, it was really strange.

Otani : Sogetsu was from the late 50s to the end of the 60s.

Ichiyanagi : If anything, it was more popular in the early '60s.

Now, I'm getting a lot of inquiries about the 1960s from America. Schools are creating archives and inviting people who can play music from the 1960s to hold concerts to deepen understanding of graphic art.

Otani : I think there is a growing interest in the 60s and early 70s around the world. It seems that more people than you would expect are coming to the Experimental Workshop exhibition. Recently, we had a concert recreating tape music, and it was packed.

■ About Ichiryu's works - Western wisdom and Eastern wisdom, and their mutual penetration

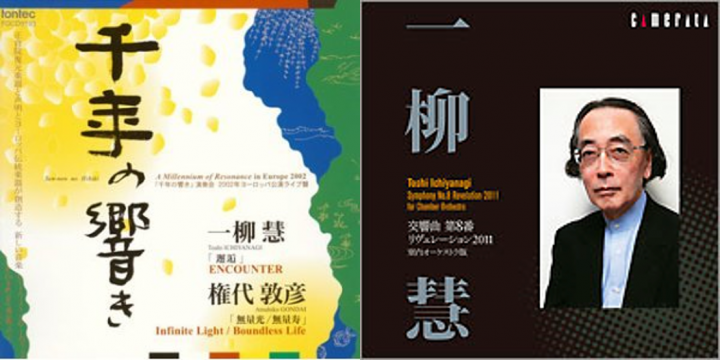

Otani : I borrowed various materials this time and listened to the music again, and I was impressed with the idea of "a thousand years of resonance" - the feeling that it is best to go back to the opening of the Great Buddha's eyes and think about it - and also with this album, Symphony No. 8 - Revelation 2011, which is very enjoyable to listen to, and does not mix Western ways of making time with Eastern ways of understanding it...

Ichiyanagi : Time and space interpenetrate each other.

Otani : Yes. I listened to each piece one by one, and as I listened to various things, I found it very interesting that there are many different senses of time, such as time associated with various senses and cultures, and that you have been permeating each piece. I would be grateful if you could tell me how you do this specifically, and also about your experiences with writing down the Eastern understanding of time on a musical staff and interacting with the player when he or she reads it for the first time.

Left: "Echoes of a Thousand Years" Right: "Symphony No. 8 - Revelation 2011"

Ichiyanagi : As you just said, the element of time is certainly very important, but the structure of thinking about music in terms of time is inevitably dominated by Western ideas. That's not necessarily a bad thing, as it was established for them (Westerners) out of necessity for a long time, and although there have been times when it has been broken down in various ways as we have progressed.

For example, the notion of impermanence that Japanese people have is not something we are particularly conscious of, but rather something that everyone has subconsciously. If we don't translate that into Western words, Westerners won't understand what you're talking about.

The Eastern or Japanese way of doing things, including the arts, is characterized by a teacher teaching his students in a very intuitive way, but it is important to think about how to understand it by replacing it with a more philosophical or logical background rather than at the level of intuition. I think that this is one of the important things that the West has taught Japan since the Meiji era. As this awareness increases, the ambiguity that existed until now will no longer be ambiguous.

Otani : It's not a teacher-student relationship, but something that can be widely read by anyone outside as a textbook...

Ichiyanagi : What I do basically is to make time and space interpenetrate each other. I learned this from Japanese architecture and gardens, for example. Time and space coexist beautifully. I wonder what would happen if I could translate that into music.

Ichiyanagi : Especially when I go to European countries and have to give lectures or talks, I always use poor English, but when I do it in English, I have to clearly organize and explain ambiguous parts and somehow be able to convey my ideas to the people there. This also helps me organize my own way of thinking.

Otani : Even between Japanese people, if they were born and raised in different places, they have to change their words so that the other person can understand, but once that kind of sensitivity is lost, it can become hostile. So it's really important for both parties to properly practice speaking in each other's language.

Ichiyanagi : I also think it’s the way we interact with nature that is particularly evident in Japan, and how this is reflected in time.

Otani : That's right. I also think that one of the great things that European civilization invented is that once you've written it down and solidified it, you can take it to another country and do the same thing there. What's more, I think that music was a great invention, being able to speak from within the body and be passed on to people (in the form of sheet music), but I think that the merits of this invention probably outweigh the demerits.

I think that the process of writing, reading, correcting it together, and then reading something that has been separated from the body and then played again is still practiced in classical music. In the case of classical music, I think that even the players have a strong sense that what is written on paper is the work.

Ichiyanagi : I think that’s the way education is.

Otani : How can we perceive music in a different way?

Ichiyanagi : A lot of people who study music don't stay in Japan but go abroad, don't they? You're absolutely right about the "merits and demerits," and I think fields like music and art that don't use words to express themselves should have the persuasive power to come up with ideas from what the object itself has, i.e. something concrete. You mentioned earlier that the Vienna group has sold out tickets for the next three years, and when you listen to how they practice, you can really see why. They talk, they consult with each other, and all sorts of things are achieved through sound.

Otani : That's completely specific.

Ichiyanagi : The substance and reality of sound without the help of words.

Otani : It would be good if paper exchanges could become the norm, based on that. In Japan, we don't have that kind of system and we just use paper.

Ichiyanagi : Exactly. I think there’s a gap there.

Otani : I'm a jazz player, and in the world of jazz music, if each person doesn't have their own unique tone, there's no point in doing it, so I find the idea of creating something by hand very appealing. But jazz is now being taught, and it's even included in university studies, like "in improvisation, you use this scale in this situation." When I see that kind of education, I don't find it very appealing...

Ichiyanagi : It’s the same with Japanese music. It feels like it’s gradually moving closer to European music.

Otani : If it's not specific, it won't be interesting at all.

Ichiyanagi : That’s true.

No, next time, I'd love to see you live. If I have the chance, I'd love to listen to you and see you perform again.

Otani : We do this occasionally in Yokohama, so please come along.

TEXT: Akiko Inoue PHOTO: Masamasa Nishino