Ozoni is fun! Ozoni researcher Hiroko Kasuya and the Ozoni Festival

What kind of ozoni do you eat at home?

Our ozoni is made with chicken stock and includes decorative slices of daikon radish and carrots. The rice cakes are grilled until lightly browned and then soaked in the stock.

I've been familiar with this flavor since I was a child and thought, "This is what ozōni is all about!" However, my concept was quickly overturned at the Ozoni Festival held in Kamakura.

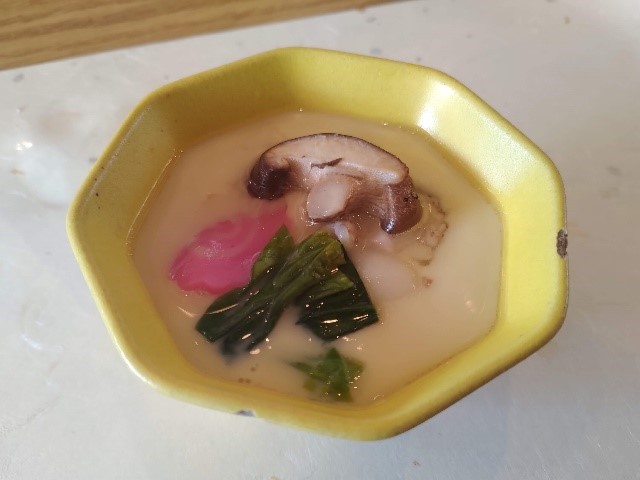

There, I encountered a variety of ozoni that I had never seen before: oyster ozoni, sweet tofu ozoni that was like a dessert, and even chawanmushi with mochi inside!

As I was amazed at the wide variety of ozoni, Hiroko Kasuya, one of the organizers and president of Ozoni-yasan Co., Ltd., an ozoni researcher, told me the following.

"Ozoni is different even within the same city or town. All over Japan, each household thinks their own ozoni is normal. Even though everyone knows that it differs from household to household, there are cases where it is completely different."

Ozoni reveals the history, culture, and daily lives of the region. We spoke to Kasuya about his passion for ozoni and the appeal of this food culture.

Kasuya's interest in ozōni began when she was in junior high school and moved to Joetsu City, Niigata Prefecture due to her father's job transfer. Until then, her "normal" ozōni consisted of clear soup with oysters or the white miso soup and sweet bean paste mochi made by her mother, who is from Kagawa Prefecture. However, when she was invited to a friend's house for New Year's, she was surprised to be treated to a brown ozōni filled with bracken and radishes. She learned that what is "normal" in ozōni varies from region to region and from household to household.

Kasuya was never able to forget the impact she had at that time, even after entering the workforce. She was busy working as a small and medium-sized enterprise management consultant, but in 2009 she enrolled in the Japan Women's University of Nutrition, where she studied nutrition and began interviewing people about zoni. Two years ago, she moved her base of operations to Kyushu, where she has been working ever since.

"Right now I'm walking around Kyushu trying to pick up old ladies (laughs). I'm going around asking 'Excuse me' here and there. You really can't know what ozoni is like in each region unless you do that. I think there are many different things that are 'normal' for each person.

In Tokyo, "Natori Zoni" is made with cabbage and chicken. So it's komatsuna and chicken, but in places like Atsugi and Hadano in Kanagawa, it changes to daikon radish, taro, green laver, and bonito flakes. In areas where fish is caught, fish isn't necessarily used, and they place value on "keeping your feet on the ground" by using root vegetables like daikon radish and taro, which is interesting.

I grew up in Kanagawa Prefecture, but our family's ozoni doesn't contain green laver or bonito flakes. What I consider "normal" is no longer "normal" if you move a little further away from the prefecture.

For example, even just looking at the shape of mochi rice cakes, various stories can be seen. I have seen on television that Sekigahara was the turning point between round and square mochi shapes. Sekigahara was a dividing line between various food cultures, and it is generally believed that square mochi was used east of Sekigahara and round mochi was used west of the city. This is because when the Edo Shogunate was born and the population of Edo increased, mass production of mochi became necessary, so the mainstream production method was to stretch the mochi after it had been made and then cut it into pieces all at once.

However, in some areas of Kagoshima, square mochi is used. This is said to have originated when the Shimazu clan, who stayed in Edo for a long time, brought square mochi back to Kagoshima. Various histories mix together and blend with local culture, creating ozoni that is unique to each region and each household.

Even within a single region, there are such huge differences, so it seems a shame that there are so few opportunities to eat ozoni from other regions. For me, ozoni is something I eat at home during New Year's, and I've had very few opportunities to eat it outside of that time. That's probably why everyone assumes that their own ozoni is the "normal" and common one.

So I asked Kasuya, "Is there an opportunity to eat ozōni other than during New Year's?"

"I think Asakura City's 'mushizoni' is a good model case, and in fact, with the help of the tourist association, there are about 10 restaurants in the area that serve it all year round. It's becoming a local specialty dish. When that happens, people who travel to the area can learn about the culture behind it. I think it's because it's home cooking that it's so unique. It's not a part of the chef's culture, but in the secluded confines of the home. I think that's why it's been able to remain a long-standing tradition. I hope that it will become possible to eat it when you travel to various places like this."

Because it is not served in restaurants, foreign tourists are unaware of its existence. I would like to make it possible for such foreigners to try it. Kasuya's desire to promote and preserve Japanese culture through ozoni is evident.

Kasuya spoke with a bright smile about his future activities.

"Starting this year, I'm thinking of focusing on food education, or more specifically, on activities to build friendships. Rather than just trying to pick up grandmothers on my own, I want to create a fun system where local people can have their stories heard by local grandmothers."

The story of how this type of ozoni came to be eaten in this region is often known by grandmothers over 90 years old who know the culture from before gas became widespread. One person cannot travel around the country in detail, so he spoke of his desire to work with local people to pass on knowledge and information about the food culture of ozoni to the next generation.

The First Ozoni Festival, which Kasuya helped plan, was a huge success, and by the time I arrived, two of the six varieties had already sold out.

Lineup:

① Hokkaido "Chicken broth zoni"

② Niigata Prefecture "Shibata Zoni"

3. Hitachiota Zoni, Ibaraki Prefecture

④ Nara Prefecture "Kinako Zoni"

⑤ Hiroshima Prefecture: Oyster Zoni

⑥ Fukuoka Prefecture "Asakura Steamed Zoni"

Each one was delicious, with different flavors, broth, ingredients, and even the shape and hardness of the mochi. As Kasuya says, being able to enjoy zoni while traveling will surely add even more enjoyment to your trip.

And if there is a second event, I would definitely like to attend again.

As I rubbed my stomach, bloated from eating ozoni, I decided to ask my grandmother for our family's ozoni recipe when I got home.