TPAM Direction Director: Interview with Tang Fu Kuen

TPAM (Performing Arts Meeting) was founded in 1995 with the aim of developing an international platform for performing arts in Asia. It provides a venue for professionals, who engage in performing arts, to get together beyond national and regional borders to share information, mutually learn and build network through diverse programs including performances, discussions and meetings. Celebrating its 20th year, TPAM 2015 was held in February and invited Bangkok-based independent curator, Mr. Tang Fu Kuen, as one of the directors for “TPAM Direction”. The program appoints producers with unique practices as directors to freely curate concepts and fresh perspectives. Mr. Tang has developed a number of projects in Asia and Europe. His program for TPAM 2015 gained good recognition for introducing a collection of works from Southeast Asia which have attracted international attention in recent years. This interview was made after the TPAM 2015 concluded.

2015.5.25 interview&text:Eiji Kobayashi

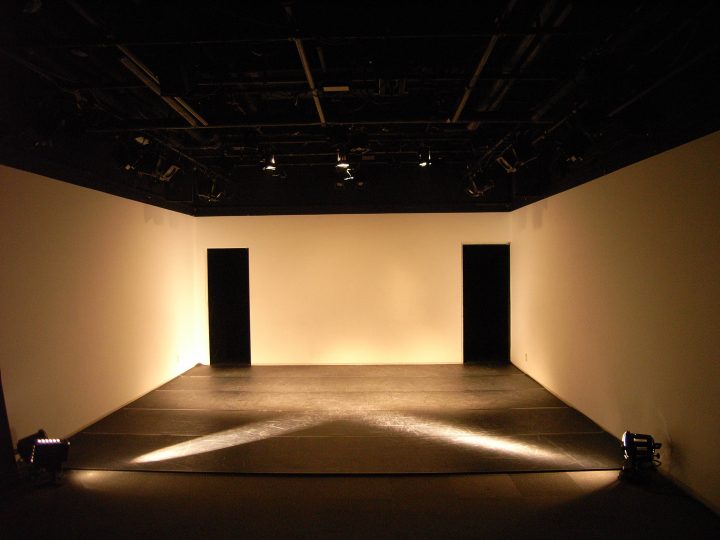

Photo: Masanobu Nishino

Translation: Mayumi Hirano

First foreign curator at TPAM

――――You are the first director invited from abroad for “TPAM Direction”. How did it happen? What were the expectations?

I have followed TPAM for 20 years and I thoroughly accomplished the programs in the last five years, so I have an understanding of the vision and evolution of TPAM to begin with. For the invitation to undertake TPAM Direction, I was tasked to tap on my knowledge to specifically spotlight contemporary artists and practices from Southeast Asia.

--What were the selection criterion for the artists?

Generally, in my curatorial approach, I build up relationships with artists through several years of dialogue. I research art works and histories, as well as artists themselves – this involves investigating their interests, methods and their processes in realizing ideas. Engaging in a sustained dialogue is absolutely essential. In the case of Eisa Jocson (Philippines), I have produced all her performances, the result of several years of trust and patience. With Melati Suryodarmo (Indonesia), I have followed her works for 8 years or so, but this was the first time and the right occasion for us to finally work together. Last November, I saw the creation of Eko Supriyanto (Indonesia) at an incomplete stage. Through dialogues with him, I felt his desire to increase the degree of perfection , and I felt a strong potential of doing so. Hence we officially commissioned him to complete “Cry Jailolo.”

On Southeast Asian-ness

―――I understand that the word “Southeast Asia” embraces a great diversity. However, if there is “Southeast Asia-ness”, what do you think it would be? If you were to define “Southeast Asia in Asia”, what would be the characteristics?

We can identify certain processes in the construction of Southeast Asia: over a century-long experience of being colonized, nationalist struggles for democracy, military dictatorship, rapid urbanization, neo-liberalism and globalisation. The shared history of violence in different forms binds the region as a common point. Still it is difficult to pinpoint a single word that can precisely contain Southeast Asia. Well…perhaps the tropical climate (laughs). Weather does influence people's perception of things.

---In the international context, I think Southeast Asia is lately producing many notable works in the fields of visual art, film and performing arts.

The international art world, in particular, has shifted its attention to Southeast Asia. However the situation for performing arts is somewhat different from the fields of video and film. The digital revolution, for instance, has enabled young filmmakers to produce and disseminate works independently In contrast, changes are slower in performing arts – there are issues related to differences in language, cultural contexts and production structures. Screen cultures are easily distributed but performance has to be remembered live, hence the reach of performing arts remains limited. From this perspective, TPAM is a pivotal platform to present Asian performing arts to the world, for its mission is clear and dedicated.

Work-in-Progress: “Host”

――――Eisa and Melati have shown their works in Europe. Is there a difference when the same works are presented in Japan? Tell me if there were differences in the public response?

Certainly. Not least in the case of “ Host ” where the Japanese audience has literacy over the theme, language, signs of “Japanese-ness” that Eisa was exploring, based on the creation residency she had experienced in Japan, during which she researched on the 'Japayuki' phenomenon of Filipino female entertainers in Japan. Hence at the post-show talk, the local audience expressed greater reaction. Much of the meaning of the work – how the gender and service are embodied and performed – are culturally-coded and were better scutinized by the Japanese audience than, say, Europeans. After the work-in-progress showing, Eisa then carried these differing cultural perceptions as critical points of consideration towards the completion of the work.

Eisa Jocson “Work in Progress “Host”” TPAM2015/Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Asia and the West: Traditional and Contemporary

――― As with the visual art, performing arts faces the issue that expressions have to be made with understanding of the value standard and structure of the West. The challenge is how to address the Asian body and its historical consciousness, for instance how Butoh emerged from Japan to the rest of the world. I was interested in how your program would deal with this issue, and I felt the potential emergence of the new.

As expected, the fusion of the two seeming contradictions – traditional and contemporary – would engender new expression. All contemporary artists suggest such rich circumstances and consequences through their work. The fundamental condition borne out of living in, under and out of the legacies of polarization and hybridity become, naturally, the place of truth and drive from which the artists articulate their realities and urgencies. This is the potent space for the development of performing arts in Southeast Asia.

Eko Supriyanto “Cry Jailolo” TPAM2015/Photo: Hideto Maezawa

---Compared to other works by Japanese artists, I felt in particular that the issue of identity was a key theme for the works in your program.

By producing performance, the artists affirm their identity. “ Cry Jailolo ” involves the minority group from the remote island of Jailolo, often perceived as 'exotic' even among Indonesians. Choreographer Eko Supriyanto demystifies and negotiates their tradition and culture by collaborating and training with them over a long period of time, then bringing them from the margin to the city. From the angle of representation and visibility within Indonesian archipelago, the work is pretty political.

Expressions only possible through the Body

--- The works in your program reserved the “margin” of interpretation for the individual audience.

The performances insist on physicalization as expressive tool, different from a mere talk or discussion on abstruse theories about the 'body'. The artistic statements are issued directly through the body as visceral instrument and affect, transmitted to the spectators over concentration and duration.

---The works can be seen online. But watching the live performance was a very different experience.

Exactly. Going back to the distinction between Asian and European tendencies, one can generally discern that Asian expressions embrace more emotionality, labor and interior energy. The dialogue performance of “ Pichet Klunchun and Myself ”, presented in TPAM Co-Production section, broached this difference by proposing the 'conceptual' West and 'intuitive' Asia on the surface, but of course it goes deeper than such an easy binarization.

――I felt that the Asian body gradually penetrates into the bodies of audience. Eisa Jocson's “Host” reconstructs Shunga three-dimensionally and evoked a strong driving force.

Yes, in comparison to the West, rituals, ceremonies, cosmological and spiritual sense hold a stronger constitution in Asian performance. They are deeply entrenched in corporeality, empathy, metaphorical and non-linguistic dimensions, and are related to selfhood. A thoughtful contemporary artist in Asia today, however, would find the reflexivity to negotiate between mind and body, thought and flesh, idea and action.

―――“ Death of the Pole Dancer ” begins with setting up a pole, and the performance feels like a small ritual.

Indeed. But what is more significant is that after setting up the pole, promising to deliver the spectacle, the artist then proceeds to refuse embodying the cliché. She rebels against the conventional female image and representations associated with pole dancing.

Eisa Jocson “Death of the Pole Dancer” TPAM2015/Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Being Independent

――Being independent seems to be an important part of your curatorial practice. What does it mean to be independent in the process of creation?

Being independent is instructive: it means listening to your own voice and to act accordingly. Yet, working alone does not mean to be disconnected, for it leads back to collaboration with artists and institutions as public interface. In the role of the mediator, the intermediary, I need to be able to operate with the strength of independence, for the necessity of speaking objection to that which I do not agree with. This is imperative to the function of being independent.

――Japan is weak in terms of independence. I have a strong respect towards the works that you have directed as well your own practice.

“Freedom” requires ceaseless dialogue. It is not about working alone but the process of engaging in dialogue, building relationships, developing and negotiating disparate elements at an appropriate pace, then finally coaxing them into meaningful fruition. I consciously persist in such a movement, taking time to collect connections, knowledge and resources, rehearsing for this “freedom” that is central to my practice.

---To conclude, please share your expectations and opinions about TPAM, if any.

I expect the future of TPAM to be an event that creates networks for mutual connections not only for relationships between “Japan and Asia” and “Japan and Southeast Asia”. It is never going to be easy because of geographical problems and historical conflicts. Without referring to utopia, continual efforts need to be made to understand and accommodate one another's differences and to share and enlarge possibilities towards safe structures for speaking and reflection.