TPAM's Singapore Focus

TEXT: Daniel Teo

→ Japanese Page

Aiming to become a regional platform for contemporary performing arts, the Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting (commonly known as TPAM) has been focusing on Asia since last year. TPAM2016 had a Singapore Focus program showcasing contemporary works by Singaporean artists. I was fortunate to be invited by the Japan Foundation to attend this year's TPAM, and as a Singaporean, I was naturally interested in what works would be presented that would represent this small city-state that has barely achieved half a century of independence.

As the program is curated by independent curator/dramaturg/producer Tan Fu Kuen, I had some idea of what works would be featured. Born and raised in Singapore, Tan has worked across Asia and Europe, notably as a festival curator, and is now based in Bangkok. His background is extensive, covering theatre, dance, film, visual arts and other artistic disciplines, from traditional to contemporary. He also has a strong interest in preserving history and traditions.

Tan is also an open critic of Singaporean art. He says a lot of work there is "almost paralyzed", limited by state funding and regulations. He also believes contemporary Singaporean artists tend to make insular works that lack clarity and are not yet ready for international recognition. "I don't think they understand enough about certain codes and logics around how contemporary art is made, which makes it difficult for it to be properly accepted in different contexts." Conversely, he likes "artists who present their work with a certain clarity and vision", like a good film director.

At TPAM, Tan said his curation "will consciously transcend the nation-state to highlight independent Singaporean artists who work with a range of collaborators and communities to articulate shared belongings and aspirations in global complexities." Regarding the artists he has chosen, he asks, "Having been brought up in an exemplary system filled with strict discipline, miraculous economic success, and multicultural life that is the envy of its neighbours, what stories of distinction and difference are they forced to tell? What worlds are they connected to (or want to be connected to)? Whose stories are they telling?"

So with Tan at the helm of the Singapore program, I expected the program to be bold, with clear and consistent direction and concepts, and to feature works that accurately conveyed the artists' style and vision, and demonstrated a deep understanding of the world outside of Singapore.

Ho Rui An, "Solar: A Meltdown"

Singaporean artist Ho Rui Ang performing the performance-talk "Solar: A Meltdown" (photo by Maezawa Hideto)

Ho Rui Ang is a Singaporean artist who uses text, media and performance to examine theory, discourse and society. One of his distinctive styles is what he calls "performative talks" - scripted lectures with multimedia footage that explore his reflections on a word or concept, such as "spectacle" in The Spectable (2014) and "wave" in The Wave (2013). In Solar: A Meltdown, performed to a full house at TPAM, he tackled "sweat."

The starting point of the talk is the sweaty back of anthropologist Charles Le Roux, or rather of his life-sized figure in Amsterdam's Tropenmuseum. A photo of a sweaty mannequin hangs to Ho's left, and to his right is a screen on which a slideshow is projected. Ho stands centre stage, slender and dressed in black. Ho begins the lecture by reflecting on why Le Roux is shown as sweaty at work, in contrast to the typical image of brown-skinned slaves sweating under the tropical sun while working hard, and the neatly dressed colonialists between them. Sweat, in essence, redeems the deified colonialists into humanity.

From here, Ho launches into a thoughtful meditation on sun, sweat and colonialism in art, history, film and media. It is a provocative journey that moves between fiction and non-fiction, the domestic and the global, and critically examines discourses on race, gender, culture and power. He draws his analysis from historical, artistic and cinematic texts, as well as his own personal memories. Finally, Ho ends Solar: A Meltdown with a recounting of his own experience of catching a glimpse of Queen Elizabeth in the middle of a crowd, waving calmly and without breaking a sweat.

Ho's delivery is clear, but he is not an enthralling speaker. When his work, Sun, Sweat, Solar Queens: An Expedition, a precursor to Solar: A Meltdown, was shown at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in India, one critic wrote, "It is ultimately a reading of a written text, and in that sense may be more persuasive in print." Indeed, Ho's text is persuasive. Full of wit and dry humor, and combined with well-chosen visual material, his talks provide an experience that is more than just boring.

The written nature of the talk, however, is sometimes an advantage and sometimes a disadvantage. For example, Ho describes a scene from The Dangerous Year in which a half-naked Mel Gibson is having a nightmare. The contrast between Ho's emotionless face and the footage of Gibson thrashing about achieves the comic effect he is aiming for. But when Ho tries to time his speech to the footage of Deborah Kerr joyously singing "The More I Know" from The King and I, it feels like he's trying too hard. Ho's talk seems to work better with multimedia behind his text than the other way around.

Solar: A Meltdown is both a masterful text and a thoroughly enjoyable performance. As a young Singaporean artist, Ho displays a keen historical and global awareness, a keen intellectual curiosity for delving into difficult questions, and an enviable ability to find humour in dark situations.

You can find out more about Ho Rui An's work on his website.

Daniel Koch/Disco Danny & Luke George "Bunny"

Luke George suspends a bound spectator in mid-air, and although not visible in the photo, Cook is also being held aloft by a spectator (Photo: Hideto Maezawa)

While some see Singapore as a country where bureaucracy and censorship can kill artists, Singaporean choreographer Daniel Kok sees it as a country of opportunity. "It's easier to be an artist in Singapore than elsewhere," he said in 2013. "There aren't enough artists, which means there's more money and space." And those opportunities allow him to travel outside the island/city-state frequently. Kok has performed throughout Asia and Europe, where he currently resides. His latest work, Bunny, was created in collaboration with Melbourne choreographer Luke George and has been performed in Singapore, Norway and Sydney before TPAM, and will be performed in New York in April this year.

"Bunny" is the nickname given to someone who is tied up in the world of rope bondage (as explained in the pamphlet), and the central question of the piece (as explained in the pamphlet) is "What would happen if everyone (in the theater) was a Bunny?" It's a thrilling question, certainly, and one that hints at what's in store for the audience.

On the surface, Bunny is a work that defies genre. In fact, it has been variously described as an "experiential dance piece," "theatrical/game play," "bondage piece," "bondage performance event," and more. The TPAM program information opts for the relatively safe description of "performance installation." But one thing is clear: Bunny is a work that uses ropes, and lots of ropes.

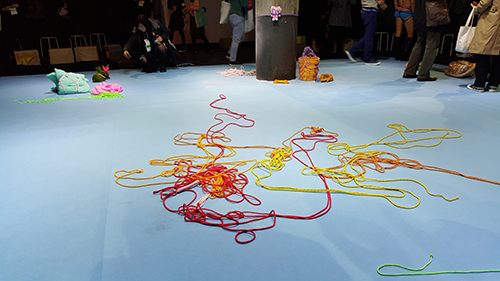

We are led into a cavernous former warehouse space on the top floor of BankART Studio NYK, where George calmly ties up a cook in the center of a performance area defined by pale blue, while a pink Hello Kitty is tied helplessly to a pillar. Surrounding the two artists, the audience is forced to notice the various objects hanging or strewn about in the performance area - tables, vacuum cleaners, rabbit figurines, buckets, and more - all tied up and hung in confusing ways with brightly colored ropes.

The sexual overtones of rope bondage performance are not shunned -- Kok and George are mostly naked except for silver tights, the former in blue underwear and a pink, short, sheer kimono. George also has yellow rope bound in a grid around her torso, and colorful braids hang from her head like dreadlocks. But beyond the eroticism, Kok says the piece is "about giving permission, about taking power."

George ties up the cock and suspends it in the air like a block of meat, and from there the interaction with the audience begins. It's a game of how willing the audience is to help the artist. It starts off surprisingly gently - George asks someone if he can tie their hands behind their back.

— but then it escalates to the most extreme acts of submission: Someone is bound from head to toe and blindfolded while another spectator guides him around the room; another is asked to whip a cock lying face down on a table.

— he does it gently, but is soon replaced by a woman who is not shy and whips the cook's bottom with great force and noise. Another woman is immobilized in more complicated ways while the cook, in a ritualistic gesture, emptys her purse and displays it neatly.

What's strangest of all is that the audience members who volunteer to perform the tasks given to them appear to be happy victims of Cook and George's pranks. Many of them have bright smiles, some giggle, but no one flinches or says "no." This submission is perhaps made possible by the mysterious, surreal atmosphere maintained throughout the performance. For example, Cook slowly wanders around the bright set playing with the props and even sprays a fire extinguisher. These eccentric actions keep the tone of the performance light and playful.

But there's also a certain malevolence in the air. George delivers his instructions in controlled tones, calmly but insistently, like an uncompromising disciplinarian, repeating the rules until they sink in. The Cook is suspended high from the ceiling, but if three spectators let go of the rope that is literally his lifeline, he will fall. And, of course, there is always the danger of being taken from the safety of their spectatorship and made the artist's plaything. This tension is made explicit when the Cook and George scan the audience for the next volunteer.

There are lulls in the performance, which is inevitable at a length of two and a half hours. Binding (and unbinding) takes time; a commenter at last year's Singapore performance said this disrupted the flow of the performance: "It creates gaps in the performance that are not rewarded enough to make up for the wait." Towards the end, Kok and George even break into a brief dance to disco music, isolating them from the audience in a way that contradicts their earlier interaction.

The end result of Cook and George's performance (photo by Daniel Teo)

But as a work that explores the relationship between artist and audience, Bunny is a masterful one. Rope bondage is an apt metaphor to expose the expectations and agreements that exist between the two. The relationship is consensual, provided both parties allow themselves to be in the same space. But which side determines the artistic content? Is the artist responding to the audience's demands, or is the former just playing with the latter? As a work, Bunny asks all these questions and goes beyond. It's bold, provocative, and (if you agree to be bound) a lot of fun.

Choy Ka Fai, SoftMachine: Expedition

The main exhibition area of Choy Ka-Fai's "SoftMachine: Expedition" (Photo: Maezawa Hideto)

Choy Ka Fai's SoftMachine: Expedition is a video installation that surveys the contemporary dance landscape in Asia. Over the course of three years, Choy interviewed over 80 contemporary dance practitioners from China, India, Indonesia, Japan and Singapore, documenting their unique dance backgrounds and practices, and what they consider to be "contemporary" dance in the Asian context.

As you enter the third floor of BankART Studio NYK, you are greeted by a huge white wall lined with photographs of the people Choi has interviewed, each accompanied by their own biography. To the left is the main installation area, where a number of video monitors and headphones are set up, playing edited footage of the interviews on a loop.

Photos of dance professionals interviewed by Choy Ka Fai (photographed by Daniel Teo)

The project's title comes from William Burroughs' experimental cut-and-paste novel, The Soft Machine, which sees the body as a hybrid of technology. Choi shares this view: "I see the body as a 'soft machine' that cuts and pastes itself into new machines. The body is full of all kinds of technology, and humans have yet to fully understand it." But the impetus for the project came from a London-based festival called Out Dance, which showcases Asian contemporary dance.

This was the sense of discomfort Choi felt when the season program "The Dance of Asia" was organized. He says, "Seeing this program, I realized that I was interested in what was within Asia, not what was coming out of Asia." This prompted him to travel to Asia to gather stories from people involved in dance. Each interview was about an hour long, and only excerpts were exhibited at TPAM, but the diversity of dance styles, practices, and philosophies from each region was still enormous.

The interviews will eventually be archived online, but that is only half of Choi's project. The other half is a more in-depth documentary video series on five contemporary dance choreographers: Rianto from Indonesia, Surjit Nongmeikapham from India, Tsukahara Yuya from Japan, and Xiao Qu and Zhou Tzu-Han from China. Over the course of two years, Choi met and interviewed them multiple times, filmed their dance work, and worked on new choreography based on their vision of contemporary dance in Asia. The result is four full-length documentary videos and four highly unique dance pieces, which have been performed in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and Singapore. At TPAM, these documentary videos and performance footage were also exhibited.

SoftMachine is an ambitious project because of its scope. After all, Asia is much larger than the five countries that Choi focuses on, and SoftMachine is a research endeavor, not a complete data set. But perhaps that is why the project is intentionally failing. Asian contemporary dance, when viewed from within Asia, may simply be a collection of disparate parts, linked geographically. Adding other elements to it may make the picture bigger and more complex, but that doesn't change the fact that Asian contemporary dance is a piece of a jigsaw puzzle that is not necessarily complete. But still, each piece is on the same board. In that sense, SoftMachine is not only an exploration of Asian contemporary dance, but also a deconstruction of the unity of "Asia" from the Western perspective. What could that be but a good thing?

You can find out more about Choy Ka Fai's work on his website .

Global Focus

During TPAM, there were two more Singapore Focus programs that I was unable to attend. One was a performance of The Observatory's seventh album, Continuum, released in 2015. The Observatory is an influential experimental art rock band in the Singapore music scene, and the music on Continuum incorporates gamelan after their two-year study of Balinese music.

The Observatory performing "Continuum" (Photo: Hideto Maezawa)

The other is //gender|o|noise\, a noise performance that "attempts to create the necessary foundations for a collective trance state." Performed by transgender experimental musician Tara Transitory (also known as One Man Nation), it explores the intersections of gender, noise and ritual. Originally from Singapore, she is now based in Spain and frequently travels between Asia and Europe to perform and lecture.

Tara Transitory performing "//gender|o|noise\" (Photo: Maezawa Hideto)

Tan's direction introduced five Singaporean works, all of them challenging, unconventional and innovative; each effectively communicating a clear vision through their own artistic form and medium. But more importantly, these five works were not just works by artists as Singaporean citizens, but by artists as global citizens. They place themselves and their art in a broader narrative, looking beyond Singapore for inspiration and collaboration; the Singapore they represent is not an island, but a city ready to engage with the outside world. In this sense, it is a bit misleading to call Tan's curation "Singapore Focused"; the spotlight he holds is a stronger, more widespread one.

*The author is in charge of research and documentation at Center 42, an arts centre in Singapore.