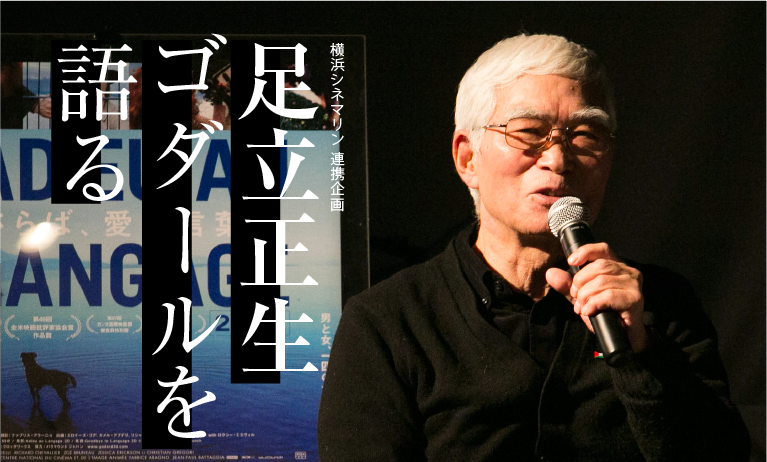

Masao Adachi talks about Godard

Text: Akiko Inoue Photo: Masamasa Nishino

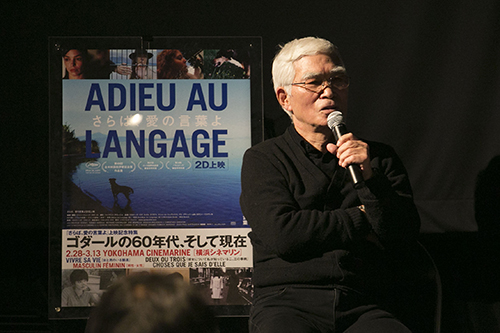

Jean-Luc Godard's "Goodbye to words of love" is currently being shown at the newly opened Yokohama Cinemarin. Godard's new work has already caused a great impact and a storm of praise around the world. There are countless perspectives and infinite interpretations to talk about Godard's work, who has been creating works while always responding to the times for over half a century since the 1960s. Yokohama Cinemarin's "Godard Special" will screen new works alongside older works, overlapping and resonating with the "now" of the 1960s and the "now" of today. There will also be a "free talk about the old and new Godard", and on the first day, film director Masao Adachi, who ran parallel to Godard in the same era, took the stage. He gave a valuable talk, including anecdotes about the Nihon University Film Research Club and the VAN Film Research Institute, as well as an episode that made him laugh when he met Godard in Cannes. This time, I would like to record the situation here as faithfully as possible.

By the way, the old work that was screened before the talk was "Women and Men" (1962), in which Anna Karina played a prostitute with a short bob. The moderator, Yuji Teraoka, a film editor, was the main focus of the talk, focusing on the contemporaneity and synchronicity of Director Adachi and Godard.

(Cooperation: Yokohama Cinemarin )

Director Adachi Masao (hereinafter Adachi): Good evening.

Yuji Teraoka (hereinafter Teraoka): Good evening. Thank you for joining us today. The film you just watched, "A Woman and a Man," is a film directed by Godard that was released about half a century ago, but I'm sure there are many people who have not seen it for a long time.

Adachi: I also watched it today for the first time in about 40 years. Actually, I love the theme song of this movie, and for some reason I cry when it plays. When I first saw this, I was still a student making movies, and the first thing that comes up is "Dedicated to B-movies." Even back then, I knew that I would be making it on a poor production budget, and this movie is about groping for the soul, so these elements overlap and it was one of the most representative movies that made a big impression on me.

Teraoka: I see. This is a work that has been shooting Anna Karina, Godard's wife at the time. Adachi also shot pink films at Wakamatsu Koji Productions in the 1960s and 1970s, and I think that taking beautiful pictures of actresses was one of the important themes. What did you think of the way the actresses were shot in "The Pavement with Women and Men"?

Adachi: Pink films have bed scenes and have to be sticky, but I couldn't make those and I was in a lot of trouble. All my senior directors made independent productions and married actresses they fell in love with, but I didn't do that very often. That's why people said I was gay (laughs).

The New Wave era

From "The Pavement with Men and Women"

Teraoka: Going back a little, in 1959, when Godard shot his first feature film, Breathless, Adachi entered the Film Department of the College of Art at Nihon University and joined the Film Research Club (hereafter referred to as Nihon University Eiken ) . I'm really curious about how Adachi reacted to this first feature film at that time.

*Nihon University College of Art Film Research Society: abbreviated as Nihon University Eiken. Founded in 1957 by Katsumi Hirano, Hiroshi Kanbara, and Hiroo Yasu (Taniyama). Succeeded by Shineiken in 1960.

Adachi: Later, the kinetic name Nouvelle Vague was given to the film, but I was influenced by the wonderful expressive power of "Breathless" by shooting with a handheld camera. At the time, I was doing a lot of things, such as how to get through the plot and storytelling, and how to use visual beauty as a language, but "Breathless" seems to have been shot without all of that, and I realized that the beauty of that removal was Godard, and I thought, "I can't take my eyes off this."

Teraoka: Did you talk about Godard with people who were aspiring to be filmmakers and were enrolled in the film department?

Adachi: I still call myself a surrealist (laughs), but I studied surrealism, so I was trying to find my own way of expression, not just language or story, in the process of changing from theater to Stanislavski to Beckett and so on. And because I placed emphasis on whether I could break through the reality in which we live, or the suffocating daily life, I started making avant-garde films. Breathless is still a normal film, but Godard started his own film criticism at Cahiers du Cinema (※) , and created this film with that touch, so there was a very avant-garde trial and error of how to dismantle the common sense of the time and create the basis of their own story.

*Cahiers du Cinema: A French film criticism magazine. It is also known for having produced French New Wave filmmakers from its writers, including Godard and François Truffaut.

Teraoka: The year 1960, when Breathless was released in Japan by Shingaiei, was also the year Adachi completed his first 8mm film, Another Day (10 minutes, black and white), which he shot in a film department class. Adachi also started making films at the same time as Godard's first feature film.

Adachi: There was a work like that. It was a boring work about a man who tries to commit suicide every day, but in the end gives up, eats a proper meal, and sleeps properly at night (laughs).

VAN Film Institute - A love triangle between Yoko Ono, Satoshi Ichiyanagi, and Anthony Cox?!

Teraoka: Changing the subject, I actually have a little surprise for you today... Do you remember a man named Kanbara Hiroshi who was at Nihon University Eiken?

Adachi: Yes. He took the initiative to create the Nihon University Eiken, and after graduating from university, I lived with him and five other people in Tokyo.

Teraoka: I'm going to deviate a bit from the topic of Godard, but today Mr. Kanbara's son is here at the venue and he told me earlier that he would like to ask Mr. Adachi a question, so I'd like to turn the microphone around for a bit!

Adachi: Are there any big surprises like this?

Teraoka: Yes. It's surprising (laughs).

Kentaro Kanbara (hereinafter Kanbara): Nice to meet you. Actually, my father, Hiroshi Kanbara, passed away two years ago, and at the wake, I first heard that my father was involved in the establishment of the Nihon University Eiken. I wanted to hear from my father's film friends, and today is a good opportunity to ask questions like this. VAN Film Research Institute (※) (hereinafter VAN), which was founded in 1960, seems to have been involved with many people, so could you tell me a little about that time?

*VAN Film Research Institute: A place for film production based on communal living, founded by Adachi, Kanbara, Jonouchi Motoharu, Asanuma Naoya, and Kawashima Keishi. It is also known as the place where postwar avant-garde artists such as Akasegawa Genpei, Kazakura Takumi, Nakanishi Natsuyuki, Kosugi Takehisa, Tone Yasunao, Iimura Takahiko, and Ono Yoko interacted.

Adachi: There was a protest against the Security Treaty in 1960, and I was always involved in that protest. (laughs)

At that time, Shineiken (※) also started making films, and it was Mr. Kanbara who took the initiative in making them. He interviewed the students on the 1960s Security Treaty protests and made a film about them. At that time, we discussed the significance of making documentaries, and that's when I started making films with Mr. Kanbara and others. I was more of a person who was fighting with the police (laughs).

By that time, everyone except for me and one other person had graduated, so we decided to do something more serious and rented a US military officer's house in Kunitachi and lived there. But we only did morning jogging and boxing, and Kunitachi was far from the city center, so we all moved to Ogikubo after that. A lot of things started to happen from there. The carpenter who owned the house built a detached house in the garden and said he was getting old so he was going to live there and rented it to us. We built an editing room there and used it as a place to stay, and all kinds of monsters (avant-garde artists) started coming and going (laughs).

*Shin-eiken: A successor organization to the Nihon University Film Research Society that was taken over at the same time as VAN was founded.

Teraoka: lol

Adachi: Kanbara-san was more like a producer who took the initiative and made money to feed us, rather than being a director himself. At VAN, Motoharu Jonouchi brought in and introduced us to art artists and poets, so we had a very rich study life. Another person who studied art the most was Inejiro Asanuma, who was the chairman of the Socialist Party and was stabbed to death, and his relative Naoya Asanuma. He was someone who could hardly drink alcohol, but he cooked for me, and when I said, "I don't have any money," he said, "I guess it can't be helped," and begged his parents' house in Koenji to lend it to me.

At that time, Yoko Ono came back from New York and started interacting with us, and her boyfriend from her time in the US, Anthony Cox, had just returned from practicing Zen meditation on the Ganges River for about three years. However, Yoko Ono was also dating Toshi Ichiyanagi at the time, so it became a love triangle, and all three of them were somehow hurt... (laughs)

Audience: lol

Adachi: I wonder what kind of fight they had. He was covered in scratches like he'd been scratched by a cat, so I asked him, "What's wrong?" He said, "I'm sorry, can you take care of this Anthony Cox?" So I took him in at VAN (laughs).

After that, at Kanbara's initiative, we decided to start a commercial company and made a lot of good works, but since both the TV station and the commercial company were paid six months later, everyone had to work with a terrible feeling until the payment was made (laughs), and in the end we decided to go bankrupt. As a result of that, I also left VAN, and everyone became independent. So, behind Toshio Matsumoto and Shingo Noda, it was Kanbara who was an active presence. If you want to hear more about the bad things, let's do it later (laughs). Oh, Hiroshi-chan also loved Godard.

Kamihara: Thank you.

"Mad Clown" and Shinjuku Culture

Teraoka: Thank you for sharing your story.

Let's go back to Godard. In 1962, the Art Theater Shinjuku Bunka (ATG) was established, and non-commercial film screenings were actively held in Shinjuku. Then, in 1967, "Pierrot le Fou," one of Godard's pinnacles, was released, but this was also the year that Scorpio was created due to Adachi's provocation (laughs). Were you able to see Godard's films at Shinjuku Bunka around that time?

Adachi: Of course I went in and out. From that time on, I was consulted about the position of ATG in the film world as a whole and its position in the cultural sphere of Shinjuku, and we started to think about it together. That's why I've seen "Crazy Pierrot" and all of that.

Teraoka: I'm very curious to know what contemporaries thought of "Pierrot le Fou."

Adachi: I really love this movie too. In the final scene, where the boundary between the sea and the sky disappears, what lies beyond that would be the world in which Nadja lives in surrealist terms, but the film ends while watching it. Godard has always pursued the idea of depicting things that do not exist, or that could only exist in the criminal world, as if they were people in their everyday lives, and in "Pavement with a Woman and a Man," he philosophically turned the social problem of prostitution upside down, but I think this is a work that culminates Godard's kind of puzzle game. However, compared to "Pavement with a Woman and a Man," "Pierrot le Fou" gave me less of a sense of my soul being taken away, and I would say that there was an aspect to it that made it easier to watch with peace of mind.

Teraoka: Does that mean that Adachi has become accustomed to "Godard language"?

Adachi: That's right.

Teraoka: By the way, one of Adachi's works is "Prayer for Ejaculation / 15-Year-Old Prostitute" (70). That film also takes a different approach from Godard's and philosophically approaches the theme of "prostitution." Simply put, it's a story about a young person who doesn't want to feel pleasure.

Adachi: This film is based on the true story of a man who committed suicide by jumping off the roof of Meiji University. In the suicide note left on the roof, he wrote, "I don't want to do an autopsy. Can anyone understand what's going on inside me?" It was a reversal of a young person's challenge to see how far they can accept the modern society and moral system that they cannot forgive, including their own desires, desires, and everything else, even if they are accepted by the intellect, language, and philosophy of "Godard's language." So it's about, "Can anyone understand what's going on inside me?"

Teraoka: That was a really piercing movie. And the aforementioned "Pierrot le Fou" was released in 1967, and the following year, 1968, Godard and Truffaut tried to cancel the Cannes Film Festival. How did Mr. Adachi receive it in Japan?

When I met Godard at the exit of the Paris subway, he seemed strange...

Adachi: Nagisa Oshima was just submitting his works to the Cannes Film Festival that year. So I encountered May in Paris and hurried back to Japan to report on it. As an extension of that, Truffaut and Godard raided the Cannes Film Festival and hijacked it, saying, "Stop the film festival as a business only!" That's how they gained a section field like the current Director's Fortnight.

*May Revolution: A popular anti-establishment movement centered on a general strike that broke out on May 10, 1968.

Teraoka: In 1971, "Sex Jack," directed by Koji Wakamatsu and written by Adachi, was invited to the Director's Fortnight of the Cannes Film Festival.

Adachi: That's right. I also went to Cannes because it was called Japanese Film Directors' Week and they were screening works by Nagisa Oshima, Yoshishige Yoshida, Koji Wakamatsu, and others who were particularly in high spirits. The anti-war movement "Peace for Vietnam" had been in full swing since the early 1970s, but I somehow thought that the Palestinian Liberation Front was the one that could win, but could not win to the end, and I was interested in that. That's why I went to Lebanon with Wakamatsu. However, about a year and a half before that, Godard had also gone to film the Palestinian Liberation Struggle. However, there was no particular news of the screening, so I asked Mr. Shibata of the French Film Company to meet Godard to find out what had happened.

Teraoka: Is that so? What did you talk about then?

Adachi: We haven't talked about anything.

Teraoka: Eh...? Is that so?

Adachi: That's what's interesting (laughs). I was waiting for a while at the subway exit of Saint-Michel, where we were supposed to meet, when Godard came walking towards me, looking around. When I asked Shibata, "You seem a bit scared, but what's the matter?", he said, "I'll explain it in detail later." So when I met Godard and told him, "I'm going to Palestine to shoot this kind of work," he muttered, "That's great, but be careful," and looked around. So when I asked him, "Are you not very interested?" he said, "I'm interested, but I'm having a serious problem right now, and I can't stay here for long like this," and he ran away, shaking off my attempts to stop him. Later, I heard that Godard's research in Palestine had caused some controversy, but if anything, there was another reason that was more important. Godard is good at telling producers, "I'm going to make this kind of work next," and getting money, but he had three of those saved up, and the producers were chasing him. So that's why we ended up talking at the subway entrance (laughs).

Teraoka: I see (laughs)

Adachi: After that, I went on a business trip overseas for a while, so I don't really know, but Godard's work on Palestine was used in the film "Here and There" about four years later.

*Overseas business trip: Here, he refers to his trip to Lebanon to work on the Palestinian issue.

Teraoka: In other words, after attending the Cannes Film Festival, you went to Lebanon and wanted to talk to Godard before filming "Red Army PFLP World War Declaration." But it wasn't particularly helpful... (laughs)

Adachi: It was like I was holding my pee and stomping my feet together, so that was more interesting. If I had a digital camera like now, I would have liked to have taken a picture.

The new film "Goodbye, Words of Love" is a confessional film by Godard

Teraoka: I should have taken a picture (laughs)

You just saw "A Woman and a Man," but before that you also saw the 2D version of the new film "Adieu au Language." I'd like to hear your impressions of that film as well.

Adachi: Yes. Is "love" the only word that has it in Japanese?

Teraoka: That's right.

Adachi: Before that, let's go back to the original topic. In "The Pavement with Women and Men," Nana, played by Anna Karina, talks to a philosopher in a coffee shop. That is a very important philosopher.

Teraoka: Bliss Balan.

Adachi: Anna Karina herself was actually a Swiss schoolgirl who loved philosophy, so Godard told her to ask him what she wanted to ask on a daily basis. Godard does that a lot. So that scene is a strange scene where the character asks something that has nothing to do with the character. Moreover, Godard, who hates Hollywood-style cutbacks, uses them, and in a sense, it's a scene where he makes it into a gag. A scene like that also appears in "Goodbye, Words of Love".

It's an adieu to words, souls, love, God, and all of those things. Most broadly speaking, I think this is Godard's most radical anarchist film. This was very interesting in its own way. So, what would happen if you really said goodbye to God, words, and love? Only nature and dogs are true, and humans are so hopeless that you can just throw them away. But I thought it would be turned upside down a bit, but it remained that way until the end. Godard has finally grown up after turning 80, and although he keeps making intellectual jokes, this is a film in which he confesses that they are meaningless. It would be better to call this a confession film (laughs).

Teraoka: I see (laughs) It's a confession film. That's a wonderful interpretation. Godard also made so many confession films at the age of 85, but is there any talk of Adachi's new film?

Adachi: Actually, I've just come back from a business trip overseas, and when I try to make a movie, the people who give me money disappear at the final stage, so I've been preparing for the past few years only to fail. I don't want to repeat that again, so I'm thinking of making it myself. I'm actually preparing one movie in earnest now.

Teraoka: Can you tell me anything more than that? (laughs)

Adachi: I wonder. If I say it in advance, I'm afraid it will be ruined again. The only thing I can say is that the title is "The Fasting Artist." It's a work written by Kafka 100 years ago, and the translation by Iwanami Bunko's Nori Ikeuchi is very good. Godard has grown up, but I haven't yet, so I think it will be a bit more of a messy movie.

Teraoka: I'm looking forward to it!

After this, there was a question and answer session from the audience. I would like to conclude this article by recording here the most memorable words that Director Adachi spoke during that session.

"I'm more than 10 years younger than Godard, but I still feel that there are things that can only be spoken of or explained through film. As long as there are things like that, I want to continue working through film, which combines images, sound, and the time we all share together."

"Make the movie you want to make, the way you want to make it." How did the words of this filmmaker, who has always believed in this, resonate with the young people and film fans who also aspire to be filmmakers and were in the audience? In this day and age when there are so many options for how to watch a movie, we should not forget that a movie is a combination of images, sound, and "time shared by everyone."

What kind of movie theater is the newly opened Yokohama Cinemarin? -From its opening to the present-

Owner Atsuko Yawata

Last December, the sad event of Yokohama Cinemarin, a long-established mini-theater in Isezakicho, Yokohama, closing its doors after a long history, was quickly followed by news of its reopening. The new owner, Atsuko Yawata, was a member of Kinema Club, a film circle based in Yokohama for 10 years, and had been working with the goal of "creating another movie theater in Yokohama." When she heard the news of the old Yokohama Cinemarin's closure, she decided to take over and operate the theater, thinking that "it is important not to lose the movie theater that exists now."

Three months after opening, the new Yokohama Cinemarin is attracting movie fans with its fulfilling programs and new facilities, and every day she is busy collecting data to attract customers and creating new programs. Although she laughs bitterly that it is difficult to balance being a housewife and running a movie theater, she says that she is trying to create programs that only a woman can do. Yawata was impressed by the film "What Are We Afraid of? Feminist Women," which was screened the other day and attracted audiences from all over Japan, at the Aichi International Women's Film Festival, and made a love call to the director to make it happen, even though it was not originally planned to be shown in theaters. As the only female owner in the city center, we can't take our eyes off her future plans. The theater is also coordinating programs with Nishimura Kyo, formerly of Kichijoji Baus Theater. A new wind is blowing through Isezakicho, which was once known as a movie street.

Yokohama Cinemarin

http://cinemarine.co.jp/”_blank

6-95 Chojamachi, Naka-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture

TEL: 045-341-3180

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ycinemarine

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/cinemarine.yokohama