Interview with Akira Takayama, Part 2 - After "Yokohama Commune"

Interview: Haruo Kobayashi (blanClass) Text: Akiko Inoue Photo: Masamasa Nishino

Indochinese refugees who were forced to leave their homes for political reasons and ended up in Japan, and Japanese people who were forced to move for various reasons and ended up in Yokohama's Kotobukicho area, where there are many cheap lodgings. Although each had a different background, they were forced to drift for some reason and ended up in Yokohama, and they met and talked at Yokohama Triennale 2014. This event was a theatrical work created by Akira Takayama as a live installation, Yokohama Commune , in which the Japanese from Kotobukicho were given the role (=setting) of "teacher" and the Asian Indochinese refugees were given the role (=setting) of "student". However, this play took on the appearance of an improvised play, and inevitably deviated from the script of "Fahrenheit 451" (※1) , which was set as a language learning material. The audience was then given a radio to peek at the Japanese language school unfolding below from the loft on the second floor of the venue, and by tuning the radio to the same frequency, they were able to eavesdrop on each other's conversations. Furthermore, in the space where the audience was, pieces to help them understand the situation were displayed as a video work, and they spent their time in that space as they wished. Wakabacho, where the venue is located, is a town with many foreign immigrants, sandwiched between the Koganecho area and Isezakicho Street, and is an entertainment district filled with international restaurants. The setting for this work was the alternative space nitehiworks, which was renovated from a former bank.

The Yokohama Commune recently came to a close with the finale of the Yokohama Triennale 2014. MAGCUL.NET interviewed Akira Takayama, the mastermind behind this work, which intertwines various elements. The interviewer was Haruo Kobayashi of BlanClass.

*1 Fahrenheit 451: A science fiction novel written by Ray Bradbury in 1953. It was cited as one of the major themes set by Yasumasa Morimura, artistic director of the Yokohama Triennale 2014, as "The Art of Fahrenheit 451: At the Center of the World Is the Ocean of Oblivion."

A "Commune" to reexamine the "here and now"

Kobayashi: Today, I would like to ask you about Yokohama Commune, which was recently unveiled at the Yokohama Triennale 2014, including my impressions of it.

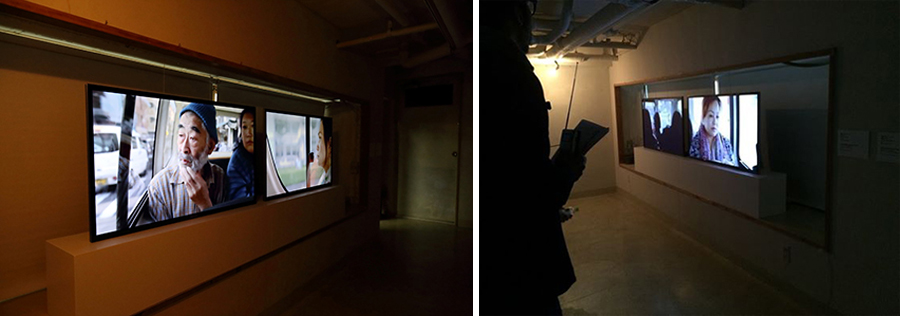

The setting for Yokohama Commune was that six Indochinese refugees (from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and six Japanese people living in Kotobukicho met at nitehiworks in Wakabacho and started a one-on-one Japanese language school, but Fujii Hikaru 's video showed them removing the monitor that had been on display at the Yokohama Museum of Art since the opening of the Yokohama Triennale and taking it to the venue, nitehiworks in Wakabacho. The video showed the Asian people removing the monitor with their own voices recorded on it in a very ritualistic way.

Takayama: For me, I wanted to show the movement of Asian people, so that it would be clear that they are the people here, by removing the monitors from the museum from Minato Mirai to Wakabacho, and then moving the people from Kotobukicho to Wakabacho. I also thought it would be nice to capture the diversity of Yokohama in the video, including the contrast between the Minato Mirai area where the museum is located and the town from Kotobuki to Wakabacho.

Kobayashi: I'm from Yokohama, so watching the video felt really strange to me (laughs). Including Fujii's unique way of filming...

Takayama: That's right. The footage exceeded my expectations and really captured the feeling of them joining together.

Kobayashi: Well, the contrast between the two towns is amazing to begin with... The way the two completely different images intersect is really well conveyed.

Installation view of Fujii Hikaru's video work capturing movement (in the space at the back of the second floor of nitehiworks) Takayama Akira / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

Left image in each photo: Moving 2 (from Kotobukicho) Right image: Moving 1 (from Yokohama Museum of Art) Video (filmed and edited by Hikaru Fujii)

Kobayashi: You touched on this briefly in the first part of our last conversation, but first, could you tell us about the relationship between the monitor footage at the Yokohama Museum of Art and the performance at nitehiworks, and the process that led to the idea for Yokohama Commune?

Takayama: The subtitle monitor exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art was like a prologue to nitehiworks' live performance.

First of all, Yokohama Commune is a work that I created with the idea of what I could take over from Tokyo Heterotopia (※2), which I did last fall. In Tokyo Heterotopia, I asked wonderful writers Masashi Ono , Wen Yourou , Yusuke Kimura , and Keijiro Suga to write texts, which I then had people who are not native Japanese speakers read. The original texts themselves were written in very well-written Japanese, but the Japanese that was read was broken. So in Yokohama Commune, I wanted to play around with the Japanese part a little more. In short, I must start by saying that the reason I chose people from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia is simply because the Japanese they speak is very different. Their language has a unique combination of vowels and consonants, and their pronunciation is high-pitched, as if it comes from above their heads. That resonated with me in an interesting way. That was the first thing that happened, and from there I started thinking about what it means to be a refugee. In the end, I came to the conclusion that refugees are "people living in a place where language, country, and everything else is not self-evident," and I decided to create a work on the theme of the Japanese they speak. The first thing I did was to interview them, and the monitor piece that was exhibited at the Yokohama Museum of Art was what I created.

*2 Tokyo Heterotopia: A theatrical production in which participants go out into the city with a guidebook and radio in hand and listen to stories about the spots they visit based on the descriptions in the guidebook.

Left: Exhibition scene at the Yokohama Museum of Art Photo: Masato Yamamoto Photo courtesy of the Yokohama Triennale Organizing Committee

Right: Removing the monitor at the Yokohama Museum of Art. Akira Takayama / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

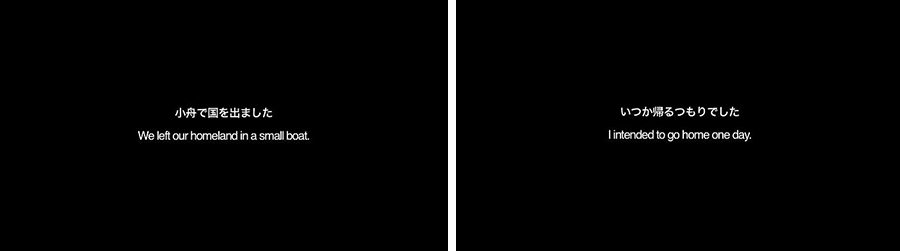

Takayama: Some of them are fluent in Japanese, while others are not. I lined them up at the same time and added subtitles in correct Japanese and English. The reason I added subtitles was because, while listening to them, I would unconsciously think, "Oh, this expression is wrong," or "I wish they'd said it like this." I think that I usually try not to think of "correct Japanese" or "beautiful Japanese" as something that actually exists, but when I'm facing people from a foreign country like them, I feel like I can't help but want to correct it. If that's the case, I thought I should make the subtitles a kind of violence. In reality, there are subtle nuances, and what they're saying has far more potential as an expression, but I deliberately inserted subtitles in a violent way, showing how it would sound if it were "correct Japanese."

An example of a monitor image (subtitles) on display at the Yokohama Museum of Art Akira Takayama / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014

Kobayashi: But languages can be like that, don't they? When I was learning English, Americans would correct me all the time... It's true that it's the most educational thing, but sometimes I think it's none of my business (laughs). Languages have to be shared, so maybe it's inevitable that things like that happen.

Takayama: At the level of everyday life, I don't care about other people's mistakes at all, and of course I often make mistakes myself. But when it comes to language education, I think it's best to teach the correct words. So I don't think that the kind of violence and authority that lurks in language education, or in all education, is simply bad... This time's Yokohama Commune also includes motifs related to migration and themes of community, but the thickest line is what I just said. For that reason, I deliberately made an exhibition of only voices, added subtitles to them, and exhibited them at the museum. By the way, the subtitle translation was done by translator Hayashi Riki .

Kobayashi: Does it start with you feeling uncomfortable with the sound of certain words?

Takayama: I myself have doubts about whether it's really enough to have only that kind of language, but if there is a society that has things like "correct Japanese" and "beautiful Japanese," and this education gradually escalates, for example, as has happened historically, it will come to the point where the person who speaks the most correct and beautiful Japanese is an old man in Taiwan. When I hear such people's Japanese, I feel an indescribable sense of guilt and embarrassment...

Kobayashi: It just remains there.

Takayama: Yes. I think that's the scar left by language education. Looking at history, I think that one of the iron rules for occupation policies and ideological control is to make the language itself correct. Japan did that too. So when I hear "correct Japanese" now, I feel quite uncomfortable. If that's the case, I think we should value movements like incorrect pidgin-like Japanese, or Japanese that has become a creole language. In that vein, I've created the "Tetsuken Heterotopia Literature Award" at the urging of Keijiro Suga, and have begun activities to protect and encourage heterogeneous Japanese, Japanese that is becoming foreign.

Kobayashi: It's the same with dialects. They gradually fade away...

Takayama: That's exactly right. The original motivation for Yokohama Commune was to create a platform where dialects, accents, and mistakes could exist a little more freely.

Members of the Yokohama Commune

Kobayashi: So, what role did the other cast members, the people from Kotobukicho (※3) , play in the production?

Takayama: The people of Kotobuki-cho play the role of Japanese language school teachers, but when I was looking for the six people to appear, I told the researcher that I wanted a variety of language levels, from people who are like doctors to people who can barely read and write. I also wanted to line up all the people who gathered on the same plane, and create a situation where they are on the same line, from beautiful Japanese to poor Japanese. Also, I think that many of the people living in Kotobuki-cho are people who "arrived" there. So I'm very curious about where they have traveled, and there are various backgrounds, such as people who have traveled around various places called "flophouse districts," people who have drifted from Kamagasaki in Osaka, and people who have finally reached Kotobuki after running out of energy. In my mind, this crosses with the fact that the Indochinese refugees finally arrived in Yokohama after a harsh journey. In other words, the motif is "Japanese language and travel," and the main motivation for creating "Yokohama Commune" is to wonder what kind of conversation they would have if they met.

*3 Kotobukicho (Kotobuki district): Naka Ward, Yokohama City. After the U.S. military took over the area in 1955, the employment office and a gathering place for day laborers moved from Sakuragicho, which led to a rapid increase in the number of "doya" (lodging houses), which continue to this day. It is considered one of the three major gathering places, alongside Sanya in Tokyo and the Airin district (Kamagasaki) in Osaka.

Installation view Top: From the second floor loft where the audience is, Bottom: From outside the venue Akira Takayama / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

Kobayashi: When I watched the live performance, I felt the strong contrast.

Takayama: They were extremely strong. They were stronger than I expected.

Kobayashi: I watched the film feeling uneasy, wondering why there was such a difference in attitude and motivation between the Asian people and the people of Kotobuki. For example, there was a scene where the Asian people were comforting the people of Kotobuki-cho by saying, "It's okay, we're still there."

Takayama: Yes, the people from Kotobukicho are supposed to be teachers and the people from Asia are supposed to be students, but the roles are reversed. When we called them, we called them by their role names, the people from Kotobukicho "teachers" and the people from Asia "students". But we purposely made it hard to tell which was which, even when we sat down, and when you actually listened to it, that didn't really apply at all.

Kobayashi: No matter how you look at it, the Asian people were teachers... (laughs) They were all so positive. In terms of moving, I get the impression that the Asian people have been through tougher situations, and I think they are under more stress living in a foreign country, but the people in Kotobukicho seemed more depressed, while the Asian people, on the other hand, were full of hope, including in the things they talked about.

Takayama: So I think the people of Kotobukicho are more reflective of reality. I don't think there are any Japanese people who have actually experienced the things that Asian people have experienced, like being rocked on a boat and drifting for days, or crossing borders while walking through a minefield. These people come to Japan and create a new environment. They are resilient.

Akira Takayama / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

Kobayashi: You mentioned "violence" earlier, but this contrast also seemed violent in a way. What did you originally want from the people of Kotobukicho?

Takayama: I told the people of Kotobukicho that I wanted them to be themselves. I was paying them, so I think it was work for them. Since Kotobukicho is a town of workers, they are very serious about getting paid to work. But of course, when they are exposed to the public, there are times when what they want to say crosses the line a little. Watching their performance, I thought, this isn't work, it's expression... and I personally really wanted to see them go back and forth between those two sides.

Kobayashi: So they are closer to actors.

Takayama: I'm an actor. I told them I was an actor in the first place. I explained the project to the Asian people better than I did to the people in Kotobukicho, so I think they understood better why I was here. So in that respect I was different from the people in Kotobukicho. It was quite difficult to get the balance right.

Kobayashi: I see. In addition to the overall mechanism, this work also has a lot of individual and complex content. For example, there are videos and a text to be read aloud (Fahrenheit 451), so I thought it was quite complicated. So, as you experience it, it becomes more and more confusing...

Takayama: For example, we changed pairs each time so that they could meet and talk for the first time, we made efforts to keep the conversation going as long as possible, and we moved the position of the clock so that it faced the audience so that they would not lose awareness of being watched as they got used to the show. We made various small adjustments.

Kobayashi: In that sense, were there any changes over the five days? I saw it on the first day, and I was wondering what would happen next.

Takayama: Yes, there was. We gradually became like friends, and I think we had a tenuous relationship of trust towards the end. So the content of the talk became more and more risqué, like, "Is it okay to talk about this...?" I could somehow tell from their breathing that they were talking about things that they normally wouldn't talk about in public. Also, some of the people in Kotobukicho had speech impediments and memory disorders, and when they recited the text, it somehow reached my ears. There was something different from an actor reciting "Fahrenheit 451" well. So I think there will be pros and cons, but I thought that this kind of existence could be a good way of doing it as a theater performance within the framework of the Yokohama Triennale. In that sense, I think I was able to present one way of doing it, where you read one book over five days as a performance of "Fahrenheit 451," and you can also incorporate as much of your personal history, memories, and recollections as you like.

To present something as a spectacle

Kobayashi: By the way, I think this was the closest to a theatrical performance among your recent works. The audience was completely focused on watching, and although it wasn't a freak show, it did feel like they were peering into the performance. How was it?

Takayama: It had been a while since I last saw it, but it was interesting. I thought that the structure of theater, with a stage and an audience, was not so bad after all. The artistic director of Yokohama Triennale 2014, Yasumasa Morimura, told me that he wanted me to do a play that would break through the art exhibition. That's why I was a little conscious of theatrical forms.

Kobayashi: Also, I thought it was really interesting that there was an upper and lower level, the first and second floors. The staff and bartenders were behind the bar counter on the first floor, and the second floor was just for the audience, which really made use of the space of nitehiworks.

Takayama: We inspected the venue and made changes to the plan. So that was a live performance that was only possible with nitehiworks, and I'm really glad we were able to do it there.

Kobayashi: We talked about Morimura earlier, but I think there were certain expectations for Takayama's work in the context of the Yokohama Triennale. I would like to hear your thoughts on what can be done within the exhibition, including going outside the museum.

Takayama: Of course, it's difficult to control the visitor's time in an exhibition compared to a play. I've finally come to understand that visitors to an exhibition look at something for a moment and then leave, so when I thought about how I could bring more of the visitor's time here, I thought that taking them outside the museum was a good idea. I thought that since they made the effort to come here, they would be more likely to stay with me. Of course, that can't be done in a museum, and I don't think they would be allowed to do it. Also, I think that people in the art world have a strong awareness of exhibiting, but in the case of a play, the stage is not seen as an exhibit. Of course, there is no sense of the actors being exhibited. But this time, because it was an art exhibition, I wanted to create a mechanism that would make the visitors more aware of "appreciation". In other words, it was like a spectacle...

Kobayashi: Presenting work at an exhibition is a difficult task. I think that visual artists have similar dilemmas to those you have about theaters, and it must be quite difficult. I thought it was interesting that this work was not called a play but a "live installation." It's a name that really conveys the feeling of a live exhibition.

Takayama: I thought that would be better. I thought it would be better if it was a zoo, but I thought it would be bad to hide the malice and cruelty of the place, so I tried to lean more strongly in that direction. For example, I deliberately included glass windows on the second floor.

Kobayashi: Oh, I see, that glass isn't always there.

Takayama: Yes. It's usually off.

Akira Takayama / Port B "Yokohama Commune" 2014 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

Kobayashi: It certainly does make it more of a spectacle. It makes the audience feel like they're complicit, like they're tuning in to the radio and eavesdropping, and they feel guilty or like they're doing something bad.

Takayama: I'll be the biggest villain. That's why I made sure to be on-site the whole time this time. In theater, the director usually comes out to the foyer and greets the audience, but I'm not good at that sort of thing, so I usually stay somewhere. But this time, I thought I had to be at the entrance to the venue for five days and expose myself.

Kobayashi: In that sense, it felt like the exhibition included Takayama-san. The scenery outside the venue, including the scene of Takayama-san greeting everyone outside, really captured the atmosphere of Wakabacho and played a part in the work. There was a limit on admission, but even while waiting my turn, I felt like I was part of the work. There was a relaxed and fun atmosphere, but also a slight sense of tension and guilt...

Akira Takayama/The future of PortB

Kobayashi: We've asked you a lot of questions about Yokohama Commune, but lastly, could you tell us about your future plans?

Takayama: First of all, I'm thinking of making a smartphone app version of "Tokyo Heterotopia". If you open the smartphone app and go to a specified location, you can listen to the story of that place. We are currently working on developing the app in partnership with Tokyo University of the Arts. As for the content, the previous writers, including Keijiro Suga, will continue to write the text, and Naoya Hatakeyama will take the photos. At first, I asked Hatakeyama to write the text, but he said, "I'd rather take the photos," so I'm really looking forward to seeing what happens. The target will mainly be restaurants, and this time we plan to expand the scope to include not only Asia but also Africa, Europe, America, the Middle East, and the whole world.

Kobayashi: There are restaurants serving food from all over the world in Tokyo. It's like there's no country that doesn't have them. New York used to be like that, but now I think Tokyo is even better.

Takayama: That's right.

The Tokyo Olympics are coming up. In my case, I don't have the opportunity to be employed and work in Tokyo. But when I'm asked, "What was your response to the Tokyo Olympics?", I don't want to just ignore it, so I want to be able to respond in some way. That's why I'm going to keep working on "Tokyo Heterotopia" steadily for six and a half years until 2020.

And the second thing is public relations.

Kobayashi: Public relations?

Takayama: In parallel with Yokohama Commune, I also participated in the Akita Art Project , where we did a project on the theme of fortune-telling called "Where Fates Intersect - The Case of Akita" . We involved seven local media companies, including television, radio, magazines and newspapers, and had each of them create content related to fortune-telling. In the end, we exhibited these and had a fortune teller come on a business trip to create a mysterious space, and I personally think that this project was an interesting invention in the sense that it connected media to theater.

Port Tourism Research Center "Where destinies intersect - The case of Akita" Exhibition view Photo: Kotoe Ishii

Takayama: So, this is unfortunate, but in this day and age, it feels like something has happened much more when the media makes a fuss than when people actually move. So, I think that traditionally, we have the idea that "public relations is a tool to put certain content into the media," but if we attach it as much as possible, not as a tool, but as public relations = content, we can do some interesting things! I thought. In other words, I wonder if we can do something like a "theater using media" that is just public relations... For me, it is a project to retranslate tour performances into a different dimension. I think that nowadays it is more important to invent routes rather than contents. I think that if public relations is not just about advertising, but the promotional activities themselves are very performative and are actually the reality of the performance, the possibilities for collaboration will expand about 100 times more than they are now.

Kobayashi: For example, companies like Dentsu and Hakuhodo, the masterminds of commercialism, are exactly like that. The information society is about selling information, not things.

Takayama: Dentsu and Hakuhodo are big models that use big money to create big content from major companies. But instead, I want to invent a model that can be done on a smaller level, with as little money as possible, and that can be used for interesting and effective PR. When it is linked to places, people, and activities and becomes a collaboration, I wonder if it will transform into something completely different... That's what I'm interested in now.

Kobayashi: Many of the old routes are no longer usable. When it comes to PR, BlanClass is in desperate need of it, but we don't have the money... (laughs)

Takayama: I think everyone is thinking about how they can do something interesting without spending a lot of money, but while everyone thinks about the content, I feel like no one gives much thought to the route through which it gets there.

Kobayashi: I think it's difficult, routes. But it's better for people to have a variety of people mixed together, so we have to do something. After all, shuffling doesn't happen because we rely on old routes.

Takayama: Yes, we need to think about the route for mixing. If that changes, I think strange things will mix together and the content will come out naturally.

Kobayashi: That may be true. I'm looking forward to future developments. Thank you for today.