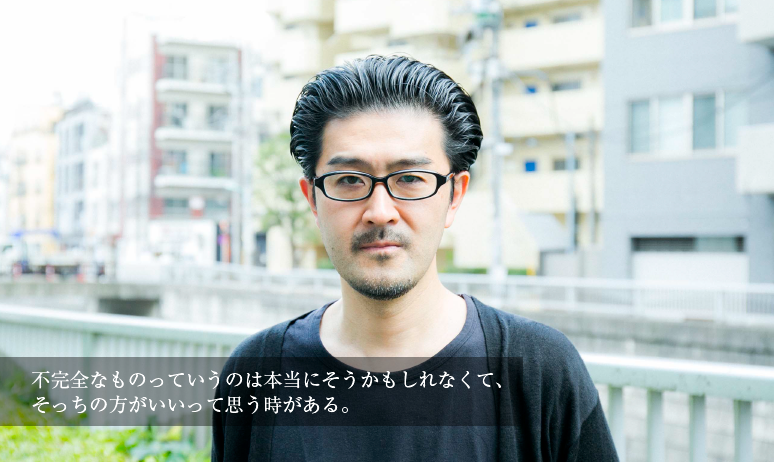

Interview: Haruo Kobayashi (blanClass)

Text: Akiko Inoue

Photo: Masamasa Nishino

Akira Takayama of Port B, who has presented his theatrical works in a unique style of touring that distinguishes him from conventional theater, such as "Complete Evacuation Manual," "Referendum Project," "Lightless II," and "Tokyo Heterotopia," will present a new work titled "Yokohama Commune" at Yokohama Triennale 2014. This work is scheduled to be performed at nitehiworks from October 30th to November 3rd, but until recently, a part of the work that serves as an introduction was exhibited at the Yokohama Museum of Art at Yokohama Triennale 2014. What kind of mechanism will be used in this work that is composed of these two elements? In mid-September, while the work was in the middle of production, we were able to talk to Takayama directly. Taking his past works into account, we interviewed Takayama about the production of this work with Haruo Kobayashi, representative of blanClass.

What is the Yokohama Commune?

Kobayashi : Nice to meet you. I look forward to working with you again. The other day, I went to the Yokohama Museum of Art to see Takayama's work.

I think the title of your past works includes the keyword "heterotopia *1 ," and I felt that this work was somewhat connected to that. In other words, the work exhibited at the museum this time focuses on "people who are considered minorities in a certain region." In other words, I got the sense that the state of minorities as seen from the majority's side, or that the relationship itself is not stable, so first of all, please tell us about the work exhibited at the museum this time and how it will be connected to the upcoming "Yokohama Commune" at nitehiworks.

Takayama : The works on display at the Yokohama Museum of Art are video monitors featuring the voices of Asian people, mainly from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and other countries, speaking in Japanese, accompanied by subtitles. They function as an introduction, like a profile, for the Yokohama Commune that will be launched at nitehiworks in the future.

Akira Takayama / Port B Yokohama Triennale 2014 exhibition view

Photo: Masato Yamamoto Photo courtesy of the Yokohama Triennale Organizing Committee

Right now it's just voices and subtitles, but at some point those people will take on a physical body and move to Kogane-cho, along with the monitors, and the general idea of the work is that it will become a physical performance piece.

Kobayashi : In other words, the person whose voice can be heard through the black monitor on display in the museum will be appearing in the performance piece.

Takayama : Yes. There are six of them in total, but we plan to invite six more people to make a total of 12 people for the performance piece.

I'm thinking of setting it up like a one-to-one Japanese language school.

In other words, six students whose native language is not Japanese and six teachers will appear at nitehiworks for three hours every day from October 30th to November 3rd (16:00-19:00 *11/3 only 15:00-18:00). By the way, we are planning to ask the teachers to be people living in Kotobukicho, Yokohama . The theme this time is "traveling", and the six students are people who have traveled from various Asian countries by various means, such as by boat or walking, while the teachers, people from Kotobukicho, are also people who have traveled quite a bit to reach the town of Kotobuki. The 12 students will meet at nitehiworks in Koganecho. We are currently thinking about what kind of lessons will be held there.

Kobayashi : The people of Kotobukicho are people who ended up here after many twists and turns. That "ended up here" or "arrived here" seems to be a major keyword for this project.

Takayama : Yes. Maybe it was temporary, but after being adrift, they are now staying in Yokohama, and they met and opened a Japanese language school. The point is that the boundaries between teachers and students are ambiguous, but in principle, the native Japanese speakers are the teachers and the Asians are the students. In reality, it is entirely possible that the students can speak Japanese better than the teachers, and the boundaries are quite ambiguous, but the students will read the same text and talk to each other about the text for five days.

Kobayashi : The performance will be held for three hours over the five days. That's quite a long time. Where and how will the audience be able to watch it?

Takayama : Nitehiworks is a mezzanine, so you can look in from there. It will be like this, and I think it will be difficult to understand what is being said, but in order to listen to the conversations taking place at each table, we will prepare a radio so that customers can tune in and listen to the conversations themselves. There are six tables.

Photo: The venue, nitehiworks (before setup)

Kobayashi : Rather than arranging the empty tables symbolically as a set, they are given this kind of function.

Mr. Takayama, you have used the technique of transmitting audio using a set of a transmitter ※4 and a radio several times, as in this case. I'm sure there are other methods in the space of a closed room, but is there a special meaning behind using a radio?

Takayama : This is a personal thing, but I've started listening to the radio a lot since the earthquake... Radio is called radiation, so it has the property of being invisible but spreading. Radio is also invisible and spreads in the same way, but I think it's quite good that one has a negative effect on the human body and the other is converted into voice. Another reason is that it uses batteries, so it doesn't need a power source and has a high degree of freedom in many ways.

Kobayashi : The audience can also interact with it. In other words, it's a device that gets the viewer thinking.

Takayama : Yes. It functions as a tool, and the act of tuning is also simply an interesting gesture.

Kobayashi : Do the audience members also get to see each other's gestures?

Takayama : That's right. There are no seats to watch the performance, so I want to make it a free space where people can watch while chatting or drinking tea. So I think there will probably be some interaction between the audience members. Or rather, I hope there will be some.

On the "perspective" when capturing a city

Kobayashi : When trying to capture a city, I think it's very important to consider what aspect of the city you want to capture. Photography and film are media that symbolize the act of capturing something, but what are the points and approaches that you pay attention to when capturing the city as a play?

Takayama : That depends on the work, but the truth is that I myself don't really know how I see the city.

Kobayashi : It seems to be a question of media, be it architecture, photography, or film, but at the same time, it's also a question of the concepts that each form has... In other words, Takayama-san cuts out the city using the concept of theater as a base, and you say that this is the opposite of what sociologists have discovered in cities. What I find distinctive is things like voices and behavior that seem connected yet separate... I feel like Takayama-san's eyes are capturing and reacting to the moment when these things overlap in a certain place. I really want to know what that is...

Takayama : To be honest, I don't really know what it is.

It's true that I often walk around the city when I'm doing research, and various ideas come to me as I'm walking. That's what almost always makes me want to try something. There's no doubt that I do this without any particular intention of seeing the city in a certain way.

Kobayashi : However, after watching it, you then bring it back to the city.

Takayama : That's right. Since theater is where I stand, I'm sure I'm looking at the city in a theatrical way. But when it comes to how to incorporate theater into the city, the first thing I can say for sure is that it's better to hide the theater. So I'm quite conscious of "trying not to make theatrical things too obvious." On the other hand, for example, sometimes it's photography, and sometimes it's a language school like this time, but I also have a strong tendency to link with fields other than theater.

Kobayashi : Speaking of photography, you worked with Shinichi Tsuchiya on "Lightless II" in 2011. He's actually a friend of mine (laughs).

Takayama : I see. It was a really great collaboration then.

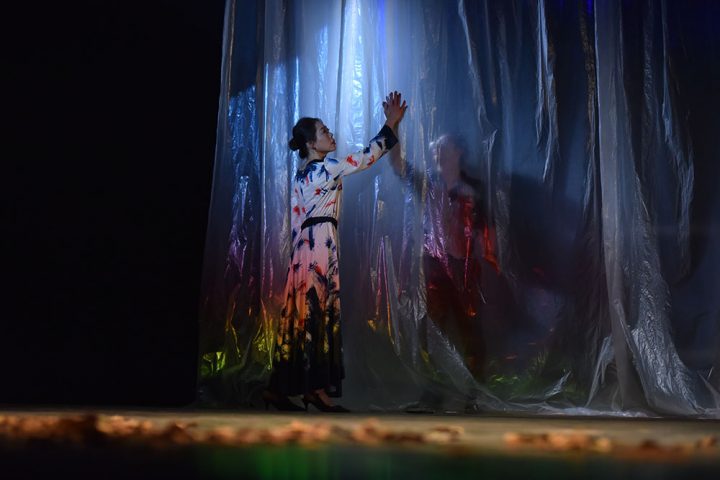

<img alt=""Lightless II" 2011 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

"Lightless II" 2011 Photo: Masahiro Hasunuma

Takayama : At that time, I collected thousands of press photos of Fukushima and photos taken in the evacuation zone, and I had Tsuchiya help me look at them. He explained things like, "So this is a press photo," or "This doesn't look like a press photo, because..." and we had endless discussions about what a press photo is, and we worked hard to refine how we could use the photos. That's how I incorporated photos into my work, but we explored ways of interacting with Tsuchiya that weren't just about having him take the photos. I like that kind of connection with other media.

Kobayashi : So that's what it means for you to connect with various media.

Takayama : I wanted them to appear in the photos to shake up the theater.

But as I continued, I began to think that it would be interesting to have a relationship where the photography was also interfering with the theater.

Kobayashi : It's like the entrance and the exit are reversed. The way you research and create things is based on theater, but when you output it, you try to transform it as much as possible. Is the fact that the entrance is always theater a kind of attitude?

Takayama : That's true. If you don't start from there, it will end up being nothing. I often think about what the standard is, but since I'm a theater person, I understand that my work is not normal from a theater perspective. But the problem is that the audience doesn't watch it thinking it's theater, and if you watch it as theater and think it's interesting because it's a little off, you'll be asked, "So what?"

Kobayashi : It's like literacy itself isn't shared at all.

Takayama : No. This is probably a big dividing line, but of course there is the approach of making something that only those who understand can understand, for a limited audience. There is an aspect to that that makes me think it's amazing if you can go that far. However, I don't go that way. I would rather eliminate the theater aspect and compete on the basis of what kind of fun and entertainment can be obtained even if you don't understand theater, so for me, the only thing that really matters is whether my work is truly interesting when it is received by the audience.

Kobayashi : When you go out into the city and create something, there are various ways to think about it, such as sociological ways of weaving a network or political ways of interpreting it, but I intuitively felt that what you are interested in is probably something that was created through economic activities. What do you think about that?

Takayama : I wasn't really conscious of it, but that might actually be the case. The reason I thought I had to deal with cities was because I thought that I needed to face the concrete target of "Tokyo" a little more, rather than the abstract "city." That was about 10 years ago. Little by little, it spread to other cities and has continued to this day.

If you look at Tokyo, it's not a city that was created by politics. For example, it started as a black market after the war, and was created by weeds that grew up from below and grew freely. In other words, it's a city that was created naturally from places where money and things flowed. For example, such networks are what make up the current Yamanote Line. So it's economic activity.

Kobayashi : In Yokohama, the areas along the Keihin Kyuko Line are a perfect example of this. The "brothel" *6 in Kogane-cho was one of them, and there were many small factories clinging to the underpass of the Keihin Kyuko line... They're all gone now, though.

Takayama : I'm somehow drawn to it.

Kobayashi : In "Urban Politics," Taki Koji writes, "Tokyo is turning itself into ruins. So even though it's sparkling, no matter where you cut it, it has the image of decay." This image is particularly strong in places like Shibuya and Shinjuku.

I thought that Takayama was working on reinterpreting cities from an economic perspective.

Takayama : When you say economy, it sounds like a broad term, but it's actually something a little lower level.

Kobayashi : Exactly. It's like what's actually happening... It's a very complicated layer, though.

Takayama : I'm really interested in the behavior and survival methods of people who are worried about things like "how am I going to make a living" or "how should I survive," and I think it was probably the same in the black markets after the war.

Kobayashi : I think Koganecho is exactly that kind of town, but in Koganecho's case, politics have had a huge influence, too. Everything was forced into the area.

Takayama : Was that after the war?

Kobayashi : After the war, the US military took over the area and conveniently crammed it into the area from Kogane-cho to Magane-cho. That's why there are so many minorities here.

Misato Yanagi *7 has written a story about that sort of thing. It's quite a fantasy, though.

Takayama : No, I thought it was interesting. It's true that I'm interested in economics. I'm not interested in towns that are organized from a certain height or depth, or cities designed by urban planners. I'm more attracted to towns that have arisen naturally, that have become like this as they have organized themselves. So I think that tendency is very strong.

Theater or City? - What is the theatrical space of the new era?

Kobayashi : As ideologies change in various ways in different regions, what was once an economy that was complete at the macro and micro levels can now no longer be fully explained on a global level, and it's hard to say that it's unique to the Internet society.

Takayama : That's right. I wanted to focus on the texture of the town, or the definite differences in the skin sensation, and of course I think that can be expressed in photography, film, or art, but listening to your story, I realized that I had been thinking about how to capture that in a theatrical way. I think that at that time, I intuitively felt that it would be difficult to bring it onto the stage.

Kobayashi : Does that mean something will be lost?

Takayama : Yes. I felt like something was going to be lost.

Kobayashi : I think that even among theater people today, there is a growing polarization of whether to make use of theaters or abandon them.

Takayama : I really like theater in theaters. After all, it has been going on for thousands of years, so it is effective to create an environment where the audience is not allowed to move and concentrate in that way. So I think there are many things that can only be done in theaters. However, when I try to do what I want to do in a theater, it becomes difficult. Intensity and centripetal force have positive aspects when creating a stage, but at a certain point I began to have doubts about them...

Kobayashi : I think it can also be seen as a positive thing that on stage we are all experiencing the same things in the same way.

Takayama : That's why, in the past, it was considered good to have a stage where you could see the same thing from any angle, and the seats at the front door were cheaper, but I've come to think that such values are not really important. Rather than that, when I thought about how to deal with things that have naturally emerged in the city, I came to think that it would be quicker to go to the city where the work is performed than to the stage, or even if I don't go there, it would be more effective to go to the city and reexamine the environment with a little trick.

Kobayashi : You could say that when you look at a city, your perspective is directed toward economic activities, but when you try to reintegrate what you see from that perspective into your work, you end up creating something that is close to an economic system. You often use the word "tourism," but tourism is about airplanes and trains, that is, how to move people. Publishing and mass media are involved, and each country strengthens its own system.

Takayama : That's true. They may have created a system or a model. But unfortunately, this is completely different from the idea of making money.

I don’t have that kind of idea at all, so it’s really troubling me… (laughs)

Kobayashi : No, I feel the same way... (laughs)

I was talking about theaters earlier, but I also run a space, and when I try to control something myself, I find it easier to plan the economics of running a single shop, for example, than within a large institution like a museum.

Takayama : That's right. I'm going to get a little carried away, but the Tokyo Olympics is coming up in seven years. If we want to show a different model to this national project, we need to reverse our standards of value to see how small things can have a big effect. Otherwise, we'll never be able to compete. It'll be like everything is just a prelude...

Kobayashi : It seems like Tokyo is in a tough spot. It seems like a bubble is about to happen... (laughs)

Takayama : I think it will happen. I think it will get bigger and bigger from now on, and some artists will jump on board. I definitely won't jump on board...or rather, I don't think I'll be allowed to jump on board, but I think I have to be careful.

Kobayashi : But even if you don't intend to be involved, I think none of us can remain unrelated to it in some way.

Takayama : I guess we can't do that. If I were to get on board with that, I would like to show that there is a model like this, where you create an app for a smartphone, and that small app can actually change the way you see the town.

Kobayashi : This may be a little off topic, but Takayama's early work "Museum Zero Hour" was a theater piece. I think you also created some stage works in the early days, but are there any similarities between the works you made back then and what you're doing now?

Takayama : Actually, there are quite a few. I did a Brecht piece right after I created Port B. It hasn't changed much since then. The play was in three parts, with Brecht's poetry collection performed in parts 1 and 2, and the audience's output in part 3. I had some professionals in the audience, so the work asks how the audience will receive it. Specifically, I had four professionals with different media - a novelist, a filmmaker, a sound artist, and a dancer - in the audience, and when the third part came, they would output on stage. For example, if it was sound, they would mix the recorded sounds from parts 1 and 2 like a DJ, or if it was a dancer, they would dance... As you can see from this early work, the core of what I want to do with theater is actually how the audience receives the theatrical work and how they can output what they receive. In other words, who is the protagonist? I wanted to create a work in which the audience is the protagonist, so it naturally took on the form it has today. However, and I don't know why, but this time at Yokohama Triennale, it was a little different, and it felt more like the customers were peeking in.

Kobayashi : I see. In a way, it's easier on the stage because it's structured.

Takayama : That's right. But doing that didn't produce any particularly interesting experiences, and it ended up being just a simple reversal of black and white, so I decided to go out to the city.

Kobayashi : But then things just get complicated. (laughs)

Takayama : I think that more complicated things are more stimulating for me and more fun to work on (laughs).

Kobayashi : Of course, Takayama's name will be on the label of his work, but the more customers who actively participate, the less clear it becomes to whom the work belongs. How do you think about your position in that regard?

Takayama : When we did the "Complete Evacuation Manual" in 2010, we only created the initial framework of creating 29 evacuation shelters at each of the 29 stations on the Yamanote Line, but by the end, the customers had become independent and started to create their own evacuation shelters. That was a very ideal for me. So, we create the initial framework, but I think it would be more interesting if the customers went beyond it, or rather, made it their own.

Kobayashi : For example, when the iPhone came out, it sold in an instant, but I think that almost no one knew what the iPhone was before they bought it. Even the people who developed the software were working without really knowing what it was (laughs). So I think what Jobs did was incredible, but he sold such an incomplete thing with a presentation like a one-catchphrase "iPhone". So everyone bought it like crazy, even though it was something that was so hard to use. But it's not that it was Jobs's thing, each person thought it was theirs. That's why I think the iPhone was so rare and a very good phenomenon. But yet, many people get very angry about things they don't understand. There may be people who get angry about Takayama's work.

Takayama : Some people in theater get angry. Or they don't pay much attention to me...

Kobayashi : But on the other hand, it's a strange society, isn't it? It seems like people are willing to spend money on things they don't even understand (laughs).

Takayama : That's true.

It may be true that something is incomplete, and sometimes I think that it's better that way. Especially in the last five years or so, I've been thinking that it would be enough to just create a base that would allow automatic generation. If you want to create something with a high degree of completion, it's easier to do it in a theater.

Kobayashi : By the way, is it possible that you will present your work in a theater in the future? I wonder if "Yokohama Commune" is similar to a theater in some sense.

You said somewhere that you thought there might be a new type of theater.

Takayama : That's right. Rather than creating theater, what I'm doing is going out into the city and creating a system that can produce a "theater," even if it's only temporary or hypothetical, in a place that isn't a theater. I think that's more important than theater.

Kobayashi : Film also started out by renting space from theaters that had previously been used for plays, so I think it's a medium that grew in an odd way, but the way it was used changed and it became a movie theater. In terms of theater, there may be a space that suits the current era, like the riverside of Edo.

Takayama : It would be fine if it was a physical space, but it's very difficult to have something like that in Japan. The location is attractive, but for now I'm thinking of going somewhere like that, and more like a theater with a layered feel.

Kobayashi : It may be the infrastructure, but whether it's Tokyo or Yokohama, there's a religious soil, or should I say a religious influence, that's deeply ingrained, and perhaps that's why the place is so open to begin with.

Takayama : Yes, that's true. And those things become more attractive the older you get.

Kobayashi : Due to government-led development in front of stations, it's becoming difficult to find places to sit down, but I hope that urban development itself will change in the future.

Takayama : I think that's what's attractive. There are interesting things in the first place, but we hide them from view with various blindfolds. I'm interested in making people realize that they were there. In other words, rather than creating something, I want to use some system to remove the layers of coverings that are there or that are inside of us, and make the hidden things visible. Rather than creating something new and questioning its strength, I want to think about things like how the relationship with the surrounding environment changes when you place something small.

Kobayashi : The experience of going out of your way to see a play is also based on a relationship.

Takayama : That's right. It was the first play I saw that I really liked, and I was able to perceive not only what was happening on stage, but also the audience around me, and I was able to enjoy it even while being fully aware of the situation I was in and how I was watching the play. So I thought, if that's what I want to do, then I've started acting.

Kobayashi : I feel that Pina Bausch's performances are very much like that.

Takayama : She doesn't create one-sided performances. I like that too.

Kobayashi : You could really see the audience's reactions, and it felt like the entire stage and audience seats were one installation.

Takayama : That's true of Pina Bausch's productions.

Kobayashi : Anyway, we're running out of time, but I feel like I've gotten to ask everything I wanted to ask. Thank you very much for today.

I hope to continue this discussion after seeing Yokohama Commune in person.

"footnote"

*1: Heterotopia: A place that is different from the everyday and separate from reality. Akira Takayama's work "Tokyo Heterotopia" was exhibited at the 2013 F/T and is a touring theatrical production that encounters a foreign land within Tokyo.

*2: Kotobukicho: the name of a town in Naka Ward, Yokohama. It is often referred to as the Kotobuki district, including Matsukagecho and Ogimachi. There are more than 100 "doya" (a temporary lodging facility) for day laborers, and it is called "doya town." It is said to be one of the three largest doya towns in Japan, along with Sanya in Tokyo and Kamagasaki in Osaka.

*3: Tandem: A language exchange in which two people with different native languages teach and learn each other's languages.

*4: Transmitter: An electrical or electronic device that sends out signals.

*5 Without Light: A theatrical production based on a play written by Elfriede Jelinek in response to the 3/11 disaster, in which Akira Takayama organizes a fictional "Fukushima Tour" by likening the urban space of Tokyo to Fukushima.

*6: Chon-no-ma: A sex shop offering sexual services operating in a former red-light district or blue-light district, or the area itself

※7: Miri Yu: ※A Japanese-Korean novelist and playwright. She lived in the Kogane-cho area. She writes many personal novels and is sometimes described as a writer who follows the tradition of the Buraiha school.