Celebrating the 60th birthday! 60th anniversary of the opening of the Concert Hall "Ask Terunobu Fujimori about the charm of the Concert Hall"

Interview, text and photo: Masamasa Nishino

Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall, the first public music hall opened in postwar Japan, is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year.

The design by Kunio Maekawa has fascinated not only local residents but also many architects. The distinctive "wooden hall," which makes extensive use of wood, was praised at the time of its opening as having "the best acoustics in the Orient." Its acoustics have been highly praised not only in Japan but also overseas.

To commemorate the 60th anniversary of the music hall, Magcal spoke to architectural historian and architect Terunobu Fujimori about the splendor of the Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall for those who have not yet visited the music hall.

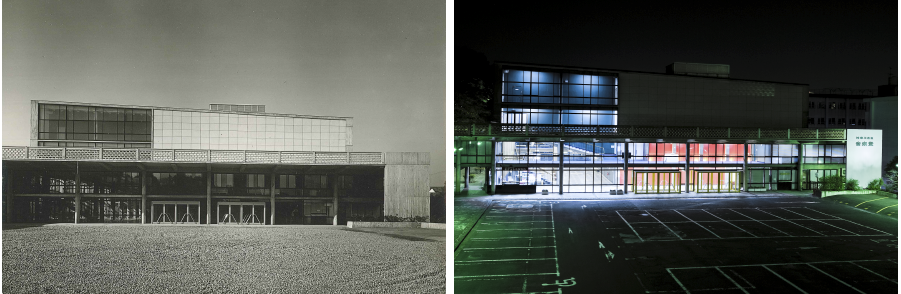

Photo on the left: Exterior of the music hall when it first opened ©Maekawa Architects

Right: Current Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall © Satoshi Aoyagi

What is Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall?

- Professor Fujimori, you often appear at the "Music Hall Architecture Tour" organized by the Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall, but for those who have not yet visited the music hall, could you tell us more about the music hall?

The Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall is one of the earliest examples of postwar architecture, and until its construction there were no public facilities dedicated to music in Japan.

Of course, there was a private hall built by Tokugawa Yorisada , but up until then, all sorts of things like music, speeches, and meetings were held in theater-like places.

However, music has the problem of "resonance," so it has to be separated from general theaters. Because of this problem, it was common overseas to separate facilities for opera and theater, but the governor of Kanagawa Prefecture at the time came up with the idea of "Let's build a facility just for music in Japan," and this led to the construction of the facility.

The governor was also enthusiastic about building cultural facilities, such as the Kamakura Museum of Modern Art in Kamakura, which was his biggest social achievement.

By the way, the music hall was designed by Kunio Maekawa, a leading figure in postwar public architecture, including the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan in Tokyo and the Tokio Marine & Nichido Building in Marunouchi.

One of Maekawa's representative works from the early post-war period is the Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall.

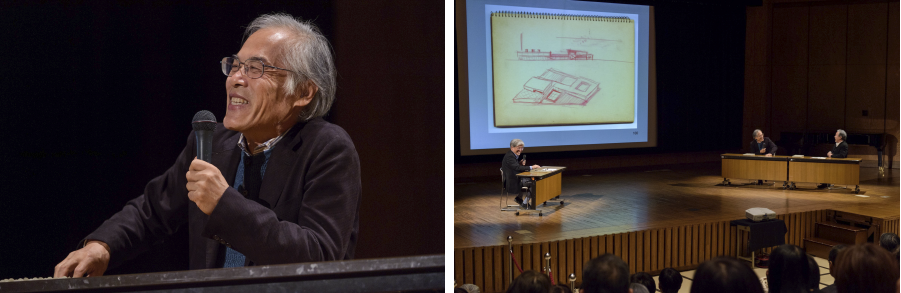

A look at the "Special Architectural Tour" held in November. The Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall holds an "Architectural Tour" every year.

The event not only included lectures, but also a variety of experiences, including tours of places that are not usually open to the public and mini concerts. Photo: © Satoshi Aoyagi

Kunio Maekawa's ideas for human scale

- We've just talked about the designer, Kunio Maekawa. What are some of the characteristics of Maekawa's work in the music hall?

First of all, as an architectural feature, the layout and floor plan are extremely well planned.

As you walk up Momijizaka towards the building, you will see the library on your left and the music hall directly in front of you.

I think the way the building suddenly appears after walking up Momijizaka Hill is very cleverly handled.

The back of the building also has a well-defined pathway, and Maekawa is known for being extremely skilled at this sort of thing.

In terms of its relationship to the library, the music hall is slightly off-center from the library, and there is space between the buildings.

The space that was left open is connected by a corridor above, and that kind of construction is a specialty of Maekawa-san, and is very clever. (※Currently, the corridor is not passable.)

Also, unlike a bank or a temple, it is not intimidating when people visit, but has the distinctive feature of welcoming visitors gently. Personally, I think it would be fine if it was a bit more imposing (laughs).

Originally, public buildings up until the war had a towering image. However, since he was an architect who was serious about civil society, I think he wanted to create an image that was more welcoming to people.

Left: The hallway connecting the library and the music hall ©MAGCUL

Photo on the right: The main entrance using the pilotis © Satoshi Aoyagi

- Did the "post-war" mindset play a major role in the image of Maekawa Kunio's designs?

I think that was very true.

The characteristic of prewar public buildings is that they were generally towering structures,

All pre-war buildings at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum are like this. They are representative of the same construction style as temples.

Maekawa didn't do that, instead he created a large pilotis using pillars, but the way the space is smoothly sucked in through the gaps in the pillars is a very post-war approach.

Of course, the pilotis was not something Maekawa came up with, it was a method used by his teacher, Le Corbusier , but the method is used skillfully to create a design that makes it easy to enter. Also, when you enter the building, there is a large space called the foyer in the music hall.

I like that foyer the most. As for the exterior, Kenzo Tange 's architecture is better because it has a more rugged look (laughs).

Incidentally, Maekawa and Tange had a master-disciple relationship, with Maekawa being the teacher but also rivals as architects, and the music hall was the design that was selected after beating out Tange in a competition.

However, when you go inside the hall, it is clear that the design is better than Tange's. Tange's halls have a powerful exterior, but

When you go inside, it seems a little too powerful for a hall.

However, Maekawa's architecture does not have this characteristic; his buildings are built to a "human scale," which is based on human measurements and sensibilities.

Another thing that I thought was extremely clever about the planning was how he made good use of the space under the floor of the music hall, and if you look at the ceiling of the second floor terrace, you can see that it is uneven and stepped.

The audience seats are above. When you go up the stairs to the second floor, one side has a ceiling that uses the space under the audience seats, and on the other side there is glass that rises up and lets in light from the courtyard.

It's a really good use of that space.

Left: The spacious foyer on the first floor. You can see that the ceiling is below the auditorium. © Satoshi Aoyagi

Right: Natural light pours in through the large windows, and the greenery in the courtyard neutralizes the coldness of the concrete. ©MAGCUL

- Indeed, when you're standing there, it's a space that doesn't make you feel like you're underneath the audience seats.

Yes, that's right. The reason why it doesn't bother me is because the ceiling opens out towards the courtyard and lets in light.

I don't think that feeling of being enveloped in the space would have been the case if it hadn't been used that way.

He also uses exposed concrete, but exposed concrete was originally thought of as being used in places like warehouses and basements, and when it was first developed, the method of using it on exteriors was frowned upon. The first person to use it was a French architect named Auguste Perret , and although Maekawa learned about exposed concrete while working for Le Corbusier and returned to Japan, I don't think he initially used it in his own works.

It started to be used after the war, but the exposed concrete is finished as it is, so it gives a rough impression. It is very unfriendly to human skin. However, even though it is an unfriendly finish, it is enhanced by bringing light into the building on a scale similar to that of a music hall and placing greenery around it.

Thanks to that courtyard, the coldness of the foyer's exposed concrete has been significantly reduced, giving it a very human texture.

Take a look at the columns in the foyer of the music hall. They are not straight but oval in shape, which is a way to make the columns look as thin and slender as possible.

Without those pillars, I think the space would really feel too strong, but this ingenious design effectively eliminates the strength of the pillars, and the exterior walls use terracuta blocks, among other small ingenious measures to minimize the strength of the concrete.

Left: The pillars are oval in shape to make them look thinner. They are poured into a wooden frame, so the wood grain remains. ©MAGCUL

Right photo: Terracuta perforated blocks used for the exterior walls ©MAGCUL

Well-thought-out materials and craftsmanship

- You've mentioned the impressive exterior and technical features that have been implemented throughout the building, but one of the hall's distinctive features is that it is a "wooden hall."

First of all, wood has a good resonance. This is a common understanding around the world, but to put it simply, just like a violin is made of wood, it's like the whole hall is inside the violin. And it has a warmth.

Furthermore, wood is an extremely superior material in Japan, so there is no reason not to use it, and in that respect the material selection has been successful.

By the way, European theaters at that time did not always use wood; they also used a variety of other materials such as plaster and stone.

So it may be quite rare to have a hall like the Music Hall where the entire surface is made of wood.

Left photo: The interior of the hall, which makes maximum use of wood. The warmth of wood can be felt even visually. © Satoshi Aoyagi

- I see. But is it possible that this selection was made for economic reasons, such as cost, in the post-war period?

I think that is certainly a factor, but I don't think there would have been any other materials that could have been used instead if wood had not been used in that hall.

Nowadays there are many other alternative materials, but I think the combination of exposed concrete and wood was chosen with the aim of softening the atmosphere of the building, and a characteristic of Japanese architecture is the use of wood in places where people will touch, even in exposed concrete buildings.

By the way, all exposed concrete buildings in Europe were made of concrete, but it was Antonin Raymond who started incorporating wood into them. Perhaps this is why Maekawa-san often started to use the combination of exposed concrete and wood.

- You mentioned earlier that you liked the design of the foyer the most, but which part of the foyer is your favorite?

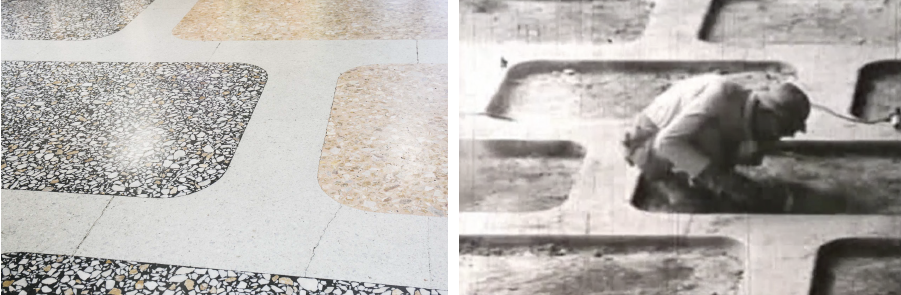

It has to be that floor finish. That terrazzo floor is absolutely stunning.

- Indeed, the floor was shown being finished in the archival footage from the time that was screened at the Music Hall architecture tour, and I was amazed at how intricately it was finished, which made it hard to believe it was done entirely by hand by skilled craftsmen.

Back then, it wasn't that expensive to hire a craftsman. Those were the good old days (laughs).

There are very few craftsmen left who can do that kind of finish now, so I think it would cost more than having the entire floor finished in titanium.

It's made with a mixture of fairly large stones, and is polished all by hand. The finish is amazing.

Left: The terrazzo floor still shines today. ©MAGCUL

Photo on the right: A craftsman finishing the terrazzo by hand. © Taisei Construction Co., Ltd. Yokohama Branch

- It's a difficult problem that there are not enough craftsmen even though the technology is advanced. Now that I think about it, it's hard to imagine nowadays that all the concrete for an entire building was hand-mixed.

That's true. But the reason we knead it by hand is because it becomes harder.

The testing method back then was really interesting; we would crack the concrete and as long as the stones inside were assimilated and cracked along with it, it was OK.

Today's concrete doesn't crack in that way.

- Are there any buildings these days that deliberately use hand-mixed construction?

No. Not only is it expensive to produce it, but the concrete is also too hard to be used in modern mixer trucks.

Pouring the paint all in is done by hand, so although it would be ideal in terms of waterproofing and durability, it would require a lot of work that is simply unthinkable today.

(*Currently, one mixer truck load is equivalent to 50 handcart loads, so one floor requires 100 mixer truck loads of concrete.)

Concrete being carried by hand. All pouring work is also done by hand. ©Taisei Kenchiku Co., Ltd. Yokohama Branch

The importance of preserving historical buildings

- The Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall was once in danger of being rebuilt, but even then Professor Fujimori issued a statement in opposition to the rebuilding.

I'm a historian, so I had a basic desire to preserve old things,

At that time, there may have been many architects who thought that old things should be demolished.

However, around the time the proposal to rebuild the music hall emerged, I think the awareness that "historic buildings should be preserved" was beginning to spread among architects.

- I think there were many opinions, both for and against, on this matter. I think there are merits to both opinions, but what do you think about the importance of preserving not only the Concert Hall but also such historical buildings?

You could make a music hall today using the same techniques, but that building has been standing for decades and has been visited by many different people, including people who have come with their significant other or people who were brought here by their parents when they were young. I think that people who come back after a long time will be moved by the sight.

When people visit a historic building, they naturally feel a deep emotion and a sense of nostalgia.

For example, when you go back to the elementary school you attended, you feel a strong sense of nostalgia. This feeling of nostalgia is unique to humans.

Other animals don't have this. For example, wouldn't you be surprised if a dog were to look back at the doghouse where it used to live and get nostalgic? (laughs)

Human emotions such as joy, anger, sadness and happiness are not necessary just to live. But when you think about why only humans can feel deep emotions like "nostalgia," it's probably because our past selves are connected to our present selves.

People who have spent a long time in a place or who visited it as children can be reminded of their past by visiting the place.

How do humans prove that the self in front of us is the same as the self we were when we woke up in the morning?It's because the view when we woke up in the morning is the same as the view we see now.

It would be really unpleasant to wake up in the morning to find a completely different view unfolding before your eyes. In other words, humans integrate what they see with their eyes and the memories in their brains, and so our sense of confirmation of the continuity of human time is very vague.

Kafka wrote "The Metamorphosis" with this anxiety as its theme, and by seeing one's own identity in terms of time, the old buildings make one feel, "I've lived for 60 years," so it's quite moving.

In particular, public buildings should not be demolished immediately even if they are slightly damaged from a practical standpoint. Europe has a high respect for such aspects, and it is unthinkable to demolish public buildings there.

- It's true that compared to Japan, I get the impression that there are many old public buildings, such as opera houses, remaining overseas.

There are no famous opera houses that are less than 100 years old, and for Europeans, public buildings serve as repositories of the memories of the people who live there.

For example, cities destroyed in war are rebuilt exactly as they were. If you go to Frankfurt, you can see that the cityscape is exactly the same as in old photographs, but there are no buildings that have been designated as cultural assets.

This is because the town was recreated using photographs of a town that was destroyed during the war.

I think that's because they understand that architecture is the temporal identity of a city and its people, and that it is proof that their culture is continuing. However, while Japan has many things that have been continued since ancient times, such as cultural customs, I feel that this awareness is a little weak when it comes to architecture.

- Today I was able to hear a lot about the wonderfulness of the music hall and the importance of preserving public buildings.

Finally, this is a bit of an extra question, but Professor Fujimori, if you were to design a music hall yourself, or if you had a hall like this, do you have a plan for it?

That's right. Music halls are designed so that the audience seats slope down towards the stage.

So I think it would be interesting if there was a hall where you could sink from above ground to below ground and still be able to sit in the audience seats. It would be a pain to get back though (laughs).

- That's quite grandiose (laughs). Thank you very much for today!

*Kanagawa Prefectural Music Hall is featured in CASA BRUTAS issue 178, "A Complete List of Modernist Architecture that Japan is Proud of" ! It is currently available in bookstores, so please check it out!