SINGAPORE FOCUS AT TPAM

Text:Daniel Teo →

Last year, the Performing Arts Meeting in Yokohama (better known as TPAM) set its sights on Asia, aiming to be the regional platform for contemporary performing arts. Enter the Singapore Focus programme at TPAM 2016, a showcase of contemporary works by Singaporean artists. I was fortunate to be at this year’s TPAM at the invitation of the Japan Foundation, and naturally, being Singaporean, I was curious to see what works had been picked to represent an island city-state just entering its second half-century of independence.

Some of my initial expectations for the works came from the programme’s curator: independent curator, dramaturg and producer Tang Fu Kuen. Tang is a born-and-bred Singaporean who has worked extensively in Asia and Europe, especially as a festival curator, and is now based in Bangkok. His work experience spans across a wide range of artistic disciplines, both traditional and contemporary, including but not limited to theatre, dance, film, and visual arts. He also has a keen interest in history and heritage conservation.

Tang is an open critic of the kind of art that is produced in Singapore. He finds most Singaporean works “meek” because of the limitations created by State funding and regulation. He also thinks contemporary artists in Singapore tend to create work that is unclear and insular, and not ready for the international stage: “Their understanding of certain codes of contemporary art making, certain logics, are not fully informed I think. It makes it hard to be properly translated into a different context for a certain consumption.” Conversely, Tang prefers the work of auteurs, “artists who already have a kind of clarity and vision in delivering their works“.

For TPAM, Tang says his curation “spotlight independent artists from Singapore who consciously work beyond the nation-state frame with collaborators and communities to articulate shared (be)longings within global complexities“. Of the Singaporean artists he selected, he asks: “Bred in a model system envied by regional neighbours for its strict discipline, economic miracle and multicultural life, what tales of distinction are they compelled to tell? What worlds do they (wish to) connect to? Whose story do they tell?”

With Tang at the helm of the Focus on Singapore programme, I expected to see Singaporean works that were bold, with clear, consistent direction and concept(s), communicated the artist’s style and vision definitively, and demonstrated an understanding of the world outside of Singapore.

Solar: A Meltdown by Ho Rui An

Singaporean artist Ho Rui An delivers his performative talk Solar: A Meltdown. Photo:Hideto Maezawa.

Ho Rui An is a Singaporean artist whose work tends towards the use of text, media and/or performance in an interrogation of theory, discourse and society. One of his modus operandi is what he calls the ‟performative talk”, a scripted lecture accompanied by multimedia visuals. These talks feature his meditations on a single word or concept, for example, spectacle(s) in The Spectacle (2014); and waves in The Wave (2013). In Solar: A Meltdown – which Ho delivered to full houses at TPAM – his fixation is on sweat.

The jump-off point of Ho’s talk is the sweaty back of anthropologist Charles le Roux, or at least that of his life-sized replica found in an exhibit in Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum. The image of the sweat-soaked mannequin hangs on Ho’s left while a large screen on which the slideshow is projected is on his right. Ho, his slight frame clad entirely in black, stands centre stage. Ho begins his lecture ruminating about how le Roux is depicted perspiring in the midst of his labours, which stands out from other portrayals of colonial masters, dressed in white and bone-dry whilst brown-skinned slaves sweat profusely from their exertions under the tropical sun. Sweat, in essence, humanises the god-like colonial oppressor.

From this point, Ho brings us on an exploration of sun, sweat and colonisation in art, history, film, and media. It is a fascinating journey, zipping back and forth between fiction and non-fiction, between the domestic and the global, critically exploring discourses of race, gender, culture, and power. Ho draws his analyses from historical, artistic and filmic texts, as well as his own personal memories. Solar: A Meltdown concludes as he narrates a memory of glimpsing Queen Elizabeth in public, serenely waving and sweat-free.

Ho, while articulate, is not the most captivating of speakers. Writing about an earlier incarnation of Solar: A Meltdown, titled Sun Sweat, Solar Queens: An Expedition, which Ho presented at the Kochi-Muziris Biennnale in 2014, a reviewer noted that “this is ultimately a written text recited; as such, it might be more compelling in published form“. And Ho’s text is compelling, indeed. It is peppered with wit and dry humour, and coupled with cleverly-chosen visuals shown during the talk, makes the entire experience much more than bearable.

The scriptedness of the talk, however, shines at some points and jars in others. For example, Ho describes a scene from The Year of Living Dangerously in which a nearly-naked Mel Gibson is thrashing about in bed while in the throes of a nightmare. The combination of Ho’s deadpan manner and the video clip of Gibson’s writhing figure was decidedly and effectively comedic. However, when Ho carefully times his recitations to a clip of Deborah Kerr gaily performing ‟Getting to Know You” from the King and I, it felt much too contrived. Ho’s talk is much more successful when the multimedia supported his text and not so much the other way around.

Solar: A Meltdown is a brilliantly written text and overall an entertaining performance. As a young artist from Singapore, Ho demonstrates a heightened awareness of the historical and the global, a sharp, inquisitive mind that ponders difficult questions, and an enviable ability to locate the humour in dark situations.

Bunny by Daniel Kok / diskodanny and Luke George

Luke George suspends a bound audience member in mid-air,

while Kok too is being suspended high towards the ceiling by three audience members (not pictured). Photo:Hideto Maezawa.

Where others see a country where artists can be tied down by bureaucracy and censorship, Singaporean choreographer Daniel Kok sees opportunities abound. In 2013, he said: ‟It’s easier to be a Singaporean artist because there are not enough artists here, which means that the country has more money and space to go around.” And some of these opportunities have frequently led him beyond the shores of the island city-state. Kok has performed his work throughout Asia, as well as Europe, where he is currently based. His latest work, Bunny, created with Melbourne choreographer Luke George, has already been places – before TPAM, the work was performed in Singapore, Norway and Sydney, and it heads to New York City in April.

‟Bunny” is a nickname given to the person being tied up in rope bondage (as the programme sheet helpfully informs). And the central question the piece asks (again from the helpful programme sheet) is ‟What if everyone (in the theatre) is a Bunny?” A tantalising question, no doubt, and one that hints at what lies ahead for the audience.

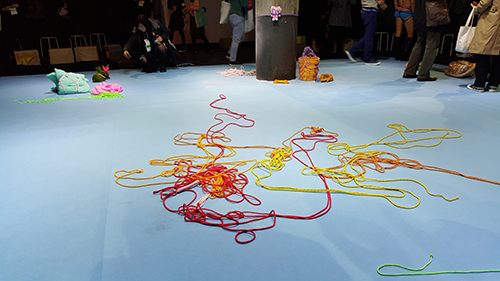

Bunny seemingly defies labels because it has been described as ‟an experiential dance work”, ‟a play“, ‟shibari work“, and a ‟bondage-performance event“. No wonder the programme sheet at TPAM settled on the somewhat safe “performance installation”. But one thing is clear about Bunny – it has ropes, and there are a lot of them.

When the audience is finally allowed in to the cavernous warehouse space on the top floor of the BankART Studio, we are greeted by George serenely binding Kok in the middle of large performance space marked out in pale blue. There is even a pink Hello Kitty plush toy helplessly trussed up against a pillar. Filing around the artists, you cannot help but notice a curious assortment of objects in the performance space – a table, a vacuum cleaner, bunny figurines, a bucket, and more – all intricately bound up in a web of technicoloured ropes.

There is no denying the sexual undertones of a rope-bondage performance. Kok and George themselves are mostly bare-skinned saved for a silver pair of tights on the former, and blue underwear and a floaty pale pink half-kimono on the latter. George is also wearing an open lattice of yellow bungee cord around his upper torso and long decorative braids hanging from his head like multi-coloured dreadlocks. But beyond eroticism, Kok said the work is ‟about giving permission, about taking power“.

And once George has Kok trussed up and suspended mid-air like a piece of meat, therein begins the interaction with the audience, a game of how much a person is willing to do for the artist. It starts off rather benignly – George asks someone to tie his hands behind his back – but soon escalates into ever more startling acts of obedience. Someone is bound head to toe and blind-folded, while another audience member leads him around the space. A man is asked to whip Kok bent over on the table – but he does it too gently and is soon replaced by a woman who is not afraid to soundly swipe at Kok’s buttocks. Another woman is immobilised on the ground with more ropes, after which Kok ceremoniously removes all the contents of her handbag and lines them neatly in a trail around the space.

Yet, the strangest thing is that all the volunteers willingly perform their assigned tasks or are happy victims of Kok’s and George’s shenanigans. Many bright smiles around and perhaps a few giggles, but no one ever gets upset or even says ʽno’. This subservience could be down to the sense of whimsy and surrealness sustained throughout the performance. For example, Kok ambles around the brightly-hued set playing with the props, even at one point setting off a fire extinguisher. These antics keep the tone of performance lighthearted and playful.

But there is also something more sinister in the air. George calls out instructions in measured tones, patiently but persistently repeating them until they are adhered to, like an unflappable disciplinarian. Kok is suspended high from the ceiling, but only because three audience members are hanging on to what is literally his lifeline. And of course, there is the threat of being called upon, to be removed from the safety of the audience and be subject to the artists’ fancy. The tension is palpable when Kok’s and George’s eyes rove about the audience looking for their next volunteer.

There are some lulls in the performance, inevitable since it is two-and-a-half hours long. Rope-tying (and untying) can take up quite a bit of time, which a reviewer of last year’s Singapore rendition found detrimental to the flow of the performance: ‟The piece is thus besieged with patches of emptiness, and the payoff doesn’t quite offset the wait.” Towards the end, Kok and George also abruptly perform a short dance to thumping disco music that cuts them off from the audience, an act seemingly at odds with the earlier reciprocity.

Aftermath of Kok and George’s performance. Photo:Daniel Teo.

But as a piece probing the relationship between artist and audience, Bunny is a very effective one. Rope bondage is a fitting metaphor to expose and explore the expectations and contracts between the two parties. The artist-audience relationship is a consensual one as both have permitted themselves to be in the same space, but who truly gets to dictate artistic content? Is the artist serving the audience’s needs, or is the former merely playing with the latter? Bunny as a work asks all these questions and more. It is a bold, evocative work, and (if you allow yourself to be un/restrained) great fun as well.

SoftMachine: Expedition by Choy Ka Fai

The main exhibition area of Choy Ka Fai’s SoftMachine: Expedition. Photo:Hideto Maezawa.

Choy Ka Fai’s SoftMachine: Expedition is a video installation charting the landscape of contemporary dance across Asia. Over a three-year period, Choy interviewed over 80 contemporary dance-makers from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Singapore, to document their unique dance backgrounds and practices, and what they thought ‟contemporary” dance meant in an Asian context.

Entering the third floor of BankART Studio, you are immediately confronted with a huge expanse of white wall on which are rows of headshots of Choy’s interviewees, each given a unique identification tag. On the left is the main installation area with a multitude of video monitors and headphones playing edited-down interview footage on loop.

Photographs of the dance-makers Choy Ka Fai interviewed. Photo:Daniel Teo.

The title of the project comes from William Burroughs’ experimental cut-and-paste novel The Soft Machine, which views the body as a pastiche of technologies. Choy subscribes to this viewpoint: ‟I see the body also as a Soft Machine that cuts and pastes and becomes a new machine by itself. The body is full of all kinds of technology that humans still have to explore fully.” But the inspiration for the project came in 2011 when Choy was left perturbed by a dance season programme in London showcasing Asian contemporary dance titled ‟Out of Asia”. He said: ‟The programme made me realise I was not interested in what was coming out of Asia, but what is inside Asia.” This realisation sent him on his expedition to collect stories from Asian dance-makers. The interviews are each about an hour’s length, even though only snippets were exhibited at TPAM. But even then they present a huge variety of dance styles, practices and philosophies from across the region.

While the interview footage will eventually be stored in an online archive, this makes up only half of Choy’s project. The other half are more in-depth documentary videos of five Asian contemporary dance choreographers – Rianto from Indonesia, Surjit Nongmeikapam from India, Yuya Tsukahara from Japan, and Xiao Ke and Zi Han from China. Choy met these dance-makers periodically over two years to interview them, film their dance practices, as well as choreograph new work based on their vision for Asian contemporary dance. The outcome was four documentary-length videos and four very unique dance pieces which have since been performed in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and Singapore. The documentary videos and performance footage were also on display at the exhibition at TPAM. A trailer of the documentary is also available to watch here.

SoftMachine is an ambitious project because of its scope. But ultimately, Asia comprises far more than the five countries Choy chose to focus on. As a research endeavour, SoftMachine is not a complete data set. Then again, perhaps the project was set up to fail. Asian contemporary dance, viewed from within Asia, is perhaps only a set of disparate parts bound together by nothing more than geography. Adding more elements may make the picture bigger and more complex, but it does not detract from the fact that it is a jigsaw puzzle with pieces that do not necessarily fit together well. But the pieces occupy the same board nonetheless. In this way, SoftMachine is not just an exploration of contemporary dance in Asia, but also a dismantling of the monolithic Asia as viewed by the West. And that can only be a good thing.

Read more about Choy Ka Fai’s work at his website.

GLOBAL FOCUS

There were two works in the Focus on Singapore programme I was unable to catch while at TPAM. The first was The Observatory’s performance of Continuum, their seventh long player released in 2015. The Observatory is an influential experimental art-rock band in the Singapore music scene. The music in Continnum was inspired by the gamelan after the band’s two-year study of Balinese music.

The Observatory performing Continuum. Photo:Hideto Maezawa.

The second was //gender|o|noise\, a noise performance billed as attempting ‟to create the foundations needed for a state of collective trance”. //gender|o|noise\ was performed by transgender experimental musician Tara Transitory (also known as One Man Nation), seeking to investigate the intersections of gender, noise and ritual. She is originally from Singapore but now based in Spain, and travels frequently between Asia and Europe giving performances and lectures.

Tara Transitory performing //gender|o|noise\.Photo:Hideto Maezawa.

Tang’s direction showcased five Singaporean works that are daring, unconventional and innovative. Each work effectively communicates a clear vision through the artistic form or media used. But more importantly, these five works are by artists who are not just Singapore citizens, but citizens of the world. They situate themselves and their art in the grander narrative, and they readily look beyond Singapore for inspiration and collaboration. The Singapore they represent is not an island, but a city that is ready to play with the rest of the world. In this respect, calling Tang’s curation a Singapore Focus is a slight misnomer; instead, the spotlight he casts is a much broader and brighter one, illuminating much more as a result.

The writer is a Research and Documentation Executive at Centre 42, an arts centre in Singapore.